Cybersecurity In-Depth: Feature articles on security strategy, latest trends, and people to know.

Is Voting by Mobile App a Better Security Option or Just 'A Bad Idea'?

Security experts say voting by app adds another level of risk, as mobile-voting pilots expand for overseas military and voters with disabilities.

Paper ballots and risk-limiting audits — the manual sampling of votes — have become the new best practices for protecting US elections in the aftermath of Russia's election meddling and hacking of voter registration databases during the 2016 presidential campaign.

Adding a paper trail to electronic voting to ensure ballots get accurately counted in the digital age may seem, well, a bit counterintuitive. But while some election officials and system security experts double down on old-school practices of paper and manual ballot counts to ensure election integrity, a hotly debated movement also is underway for casting votes via personal mobile devices.

Figure 1:

Election jurisdictions in several states have tested mobile app-based voting for state, federal, county, and municipal elections — mainly military and civilian residents stationed overseas to cast votes from their smartphones and tablets in lieu of traditional email, fax, and paper methods. West Virginia offered mobile voting for both state and federal elections in 2018; Utah County, Utah and Denver County, Colo., offered it for their municipal elections this year. In all, 29 counties across five states have tested Voatz's mobile-voting app in official elections.

The underlying goal of mobile voting, its organizers say, is to encourage more voter participation by making the process easier and more accessible. Oregon's Jackson and Umatilla counties, as well as Utah County, recently extended their mobile-voting pilots for municipal general elections to include civilian stateside voters with disabilities.

Critics argue that this method of voting is inherently risky and insecure: Vulnerabilities are regularly unearthed in both Android and iOS, and cybercriminals and nation-state actors increasingly are waging mobile exploits to target their victims.

Mobile voting is "a bad idea," says Ibrahim Baggili, who is the founder and co-director of the Cyber Forensics Research and Education Group and an associate professor at the University of New Haven. "Until we can have secure devices for every voter, I don't think it's worth it," he says.

More Secure Than the Status Quo?

But proponents of mobile-voting maintain that the apps and process are more secure and private than the standard practice of sending PDF-based ballots via unencrypted email to military personnel overseas.

Some mobile-voting technology contains built-in security and vetting functions: The Voatz app used in Colorado, Oregon, Utah, and West Virginia, for example, comes with three layers of user authentication, and its blockchain distributed-ledger technology encrypts the data and provides privacy and an audit trail, its proponents say. The app also scans the voter's device for malware and proper Apple or Google digital certificates before allowing the voter to cast his or her ballot.

Sheila Nix, president of Tusk Philanthropies, the nonprofit that's funding the Voatz-based mobile-voting pilots in the four states, says she's well aware of security concerns about mobile voting, which is why the group has hired outside security experts to test and evaluate the security of the technology.

"My overall theory is we don't want to promote something that's not secure. Then our goal backfires," she says.

Snake Oil?

Mobile voting seems like a natural progression for a society of users who already bank, shop, share, and communicate via their smartphones. Some experts believe its adoption, in some form, may be inevitable in the future despite the current misgivings about its security. But mobile technology is fraught with vulnerabilities, and blockchain security remains a big question mark, opponents say.

Among the critics of mobile voting is DEF CON Voting Village organizer Harri Hursti, who believes mobile voting won't survive beyond the pilot phase.

"It's going to be fizzled out after all the money has been milked [from it]," he says. "It's truly profitable for companies promoting this. The whole idea of snake oil always [sells] well."

Hursti was one of the first researchers in the world to hack voting machines. As part of a 2006 project organized by a nonprofit election watchdog group called Black Box Voting, Hursti, along with Hugh Thompson, found major security vulnerabilities in Diebold voting machines. The project was profiled in the HBO documentary Hacking Democracy.

He says he worries about the risk of voter coercion in mobile voting; merely having your smartphone as your personal voting machine leaves a voter vulnerable to pressures from other individuals. And smartphones are far too prone to malware and other cyberthreats to be considered a reliable voting tool, he says.

"Just because Apple improved security doesn't mean you're secure as a user," he says.

Security services and consulting firm ShiftState Security has been analyzing the Voatz mobile platform on behalf of Tusk. Jason Truppi, co-founder of ShiftState and a former FBI cybersecurity agent, says there's no such thing as unbreakable security, and he definitely gets why critics are wary of mobile voting.

"I've seen all the threats," says Truppi, referring to his past work investigating nation-state and cybercrime breaches while with the FBI and in the security field the past two decades. "So if you want to talk skeptical, I'm as skeptical as the industry itself."

But Truppi also believes voting methods are gradually changing. "It's hard to imagine a world that's still going to the [physical] polls 10 to 15 years from now," he says. "Mobile voting is an eventuality. Why not solve some of the [security] problems now?"

Coming into Focus

It wasn't until the past three years that the security of voting and elections received much public attention at all. That changed dramatically after the 2016 presidential election and was punctutated by the DEF CON hacking conference's maiden Voting Village event in 2017, where it took just 90 minutes for the first two security researchers to hack voting machines using flaws they discovered.

Marian Schneider, president of nonprofit Verified Voting, told attendees at a presentation during the 2019 Voting Village this past August in Las Vegas that mobile device vulnerabilities could be abused in the voting process — and voters' personal information could be exposed.

"I understand the worthy desire to increase voter participation and to remove a barrier to voting," Schneider said. "But voting on my phone is not the way to do it. It's opening the door to the county and state to an attack."

She noted that when the mobile app sends the vote back to the voter to ensure its accuracy, this also opens up privacy holes to the voter. "How is the app developer not able to see it," as well as the biometric and other data provided by the user, she argued.

Schneider's organization has been one of the leaders in pushing for paper ballots in elections as a way to validate vote counts, and one of its board members in May co-authored a report calling out Voatz for a lack of transparency in providing the details of its blockchain implementation.

A researcher who was one of the first to hack voting machines in the Voting Village in 2017 also considers mobile voting too risky. "It's a good first step, but there are a lot of things missing," such as a privacy layer atop the blockchain, says Carsten Schuermann, an academic expert in election security who has been studying election security for a decade.

Schuermann, a computer scientist at the IT University of Copenhagen in Denmark, compromised a WinVote voting machine on the Wi-Fi network at the 2017 Voting Village, exposing real election and voting data that was still stored on it.

How the Voatz App's Security Works

But supporters of mobile voting say at least some of the vendors have been building in security. The Voatz app, for example, scans for vulnerabilities and signs of compromise or vulnerability up front: If the Voatz app discovers that the smartphone has been compromised, it won't allow the user to vote, the company says. If the app passes the security tests via Voatz and third-party tools provided via the app, it then authenticates the voter on their phone using either a fingerprint or facial recognition.

Next, the voter scans their government ID – typically a driver's license or passport – and takes a video selfie for further authentication. He or she then touches the fingerprint reader on the phone to verify the smartphone is in the hands of the voter. The Voatz app matches the selfie with the picture on the voter's ID and confirms whether they are eligible to vote by checking registration information.

Voters can use their own additional factor of authentication, such as their Apple Watch, Google Authenticator, and Yubikey. But most users still rely on SMS or email as the additional authentication factor, according to Voatz co-founder and CEO Nimit Sawhney.

Voatz uses a 32-node blockchain infrastructure across Amazon AWS and Microsoft Azure, each hosting 16 of the nodes across the US. Cloudflare is among several companies that provides distributed denial-of-service defense services, and Voatz says the system employs certificate pinning, end-to-end encryption, and multifactor authentication for the infrastructure nodes. Encryption of the voting information in transit is TLS 1.2 and AES-256-GCM, and sensitive data stored on backend systems and nodes also gets encrypted.

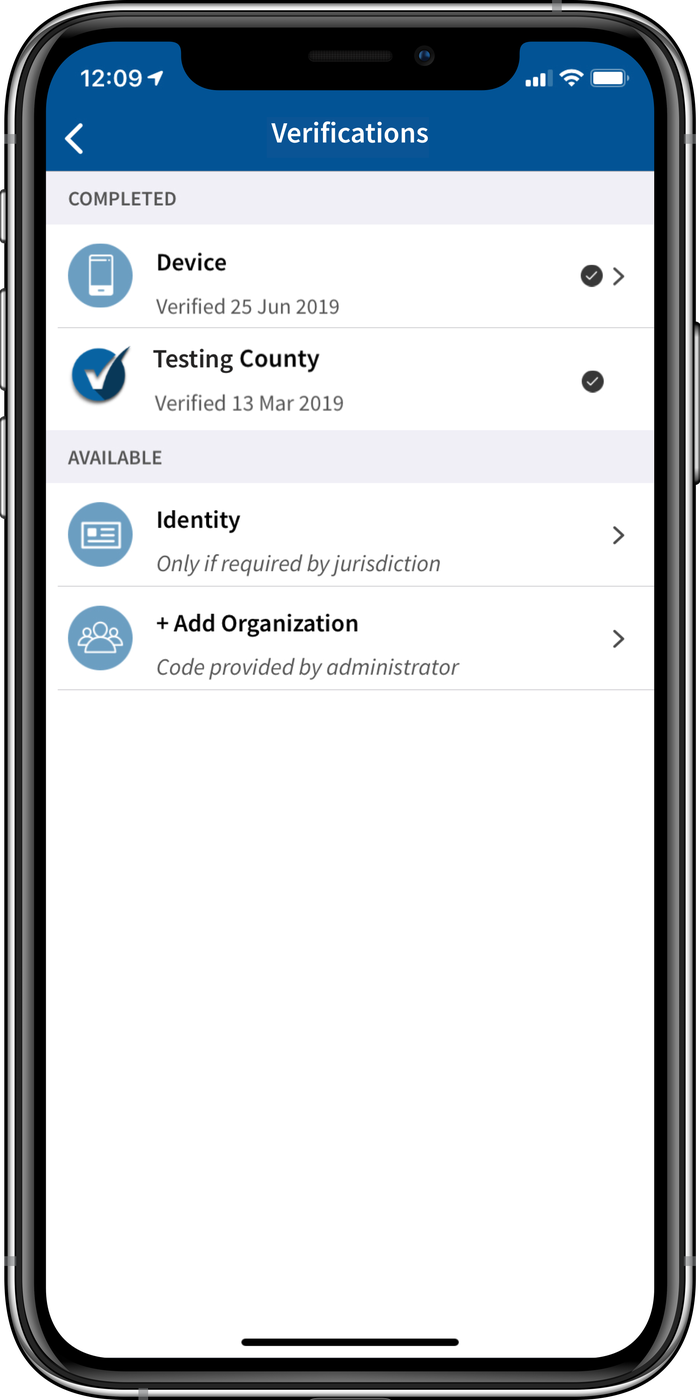

Figure 2:  Voatz mobile-voting app interface.

Voatz mobile-voting app interface.

Each ballot cast also generates a paper ballot as backup. "It's marked and put in a digital lockbox protected by blockchain, and [election officials] unlock it on election day, print it out on ballot paper, and scan it into a tabulator," explains Sawhney.

At least two officials have encryption keys to the voting information via Voatz's admin portal, from where they also download the PDF with all ballots marked, and voters get a digital "receipt" of their vote. Election officials can use the paper ballots with the digital ones to perform post-election audits, he says.

More Work to Do

But Sawhney, as well as security experts who have studied mobile-voting technology, consider mobile-voting security still a work in progress. "We're excited more jurisdictions are willing to take a leap of faith and try out our system," Sawhney says.

So far, Voatz has been used for some 53 elections, including non-governmental ones in universities and nonprofits. The app also has undergone some third-party scrutiny: ShiftState recently delivered to Tusk its recommendations for how to run future mobile-voting programs securely, after evaluating the Voatz app and process as well as some other mobile-voting vendors, including Democracy Live and SmartMatic. (Voatz was the first voting app Tusk has worked with.) ShiftState's Truppi says his team will help Tusk create software requirements, possibly some type of open audit process, to scrutinize the technologies, including blockchain, and to determine where and how to include open source technology for voting.

"It's not about whether existing technologies are good enough: [It's] how is the future of elections actually going to be able to run [securely]?" he says.

Truppi's team found areas of the mobile-voting app and platform security that could be improved as well, which he would not reveal publicly. Tusk has chosen a third-party code auditing firm, which will perform an assessment of the software. Voatz, meanwhile, also recently added a bug bounty program via HackerOne.

Truppi says he's a realist in that he knows all software has vulnerabilities. He applauds the level of authentication and verification in Voatz.

"Your bank is not doing nearly the [same] level of authentication and verification of users" in its mobile apps, he says. Some of those use only two-factor authentication or just username and password, while Voatz uses various layers — driver's license, username/password, token, and facial recognition. "With all of those [factors], I think their authentication is very solid," he says.

Denial-of-service (DoS) attacks are a legitimate risk with mobile voting, he notes. "Tusk and our team have been looking at backup methods" for an infrastructure failure in the event of a DoS attack on the mobile-voting system, Truppi says.

As for the blockchain piece of the process, he says that's less of a worry, security-wise. It's just one component of the voting process, he notes, which also includes the identity, verification, and validation security steps. "Blockchain in this case is for the particular app it was built for: to distribute the database so it's harder to attack remotely ... and it also has cryptographic proof of auditing every transaction."

The main security risk, Truppi notes, is at the interface with the election jurisdiction, he says, where the ballot gets printed, with a hash or encrypted key on top, and then gets stored there and ultimately scanned into ES&S ballot scanning systems. Then the process is out of Voatz's hands.

Truppi says he believes the Federal Election Commission (FEC) ultimately should provide guidelines for securing mobile-voting infrastructures. Among the issues that need to be more clearly defined, he says, are the minimum level of encryption for ballots, both at rest and in transit.

"I've talked to Tusk about building a framework like that," he says.

No Rush

A Denver-based cybersecurity nonprofit called the National Cybersecurity Center (NCC) audited the mobile-voting pilot for the city's municipal elections this spring that allowed military and citizens overseas to vote via their smartphones with the Voatz app, which voters can download on Google Play and Apple Store. Forrest Senti, director of government affairs at the NCC, says the pilot's goal was to remedy problems with the current methods of sending ballots, unencrypted, via email and fax.

It's unclear, though, whether mobile voting could expand beyond its current narrow scope of overseas voters and those with disabilities, Senti says. "One way we can figure out if mobile is a solution is to keep testing it and deploying it," he says. NCC recommends that the US Department of Homeland Security (DHS), as well as security researchers, dig into mobile-voting technology to root out security vulnerabilities and weaknesses.

Ideally, the apps could be included in the DEF CON Voting Village for hackers to test as well, he says. "We've talked about it, and it would be interesting to see if setting up a live demo would be possible," he says.

Voatz's Sawhney also supports a gradual rollout of mobile voting. The goal, he says, is to introduce mobile voting slowly and methodically. Close to 90,000 voters overall have cast their ballots via Voatz in various types of elections, including more than 700 overseas military and civilians.

"We don't want to do it too fast," he notes. "So I think dividing the process into baby steps is important. The first was military and overseas citizens, and next was the disability [community]."

Voatz hopes to open up mobile voting after 2021 to more communities, including students away at college who want to vote absentee. "We are very optimistic" of the future of mobile voting, he says.

Attacks on the Horizon

Sawhney's company also is working on improving its platform to face evolving and expanding security threats, he says. "Our security infrastructure needs to be able to handle that. So we've kind of been working on simulating some of those" threats already, Sawhney says.

Voatz's current method of monitoring its voting infrastructure 24/7, for example, won't be sufficient if mobile voting expands beyond the pilots. "We will need help from other parties as well: election jurisdictions ... other stakeholders in the ecosystem," he says.

The hope is that mobile service providers might work with Voatz in monitoring for threats, as part of a collaborative effort, he says.

Not surprisingly Voatz already has experienced attack attempts on its infrastructure. One incident during the 2018 midterm elections in West Virginia recently went public after the FBI opened an investigation into the attack. An intruder attempting to hack the app was spotted by Voatz, who reported it to the state election officials after thwarting the attacker.

The attacker appeared to be coming in from an unrelated geographic location, which is what initially set off alarms for Voatz. According to a CNN report, a University of Michigan student attempted to hack the app for an election security course. Sawhney declined to comment on the report but says it wasn't the first attack attempt his team has thwarted.

The attacker in the West Virginia election tried to register to vote but wasn't on the verified voter list, so he didn't get past that step. He then downloaded the app on another device and attempted to connect his smartphone to a computer, which raised more flags, Sawhney says. "He didn't get a chance to do anything more than register, so it's hard to determine what his real intent was," he says.

Sawhney says most of the Voatz team comes from a security background.

"I used to part of a threat team in my past life," he says, adding that he's interested in collaborating with the DEF CON Voting Village to test the mobile-voting system and provide feedback on their findings. "We would love any help improving the system," he says. He says he wants to be sure, though, that testing in the Voting Village wouldn't be for creating a "scandal" or bashing the election industry.

But the nagging security implications of voting by mobile app loom large for several members of the cybersecurity community. Chris Wysopal, co-founder of software security firm Veracode, says he understands the convenience of mobile voting and how it could garner greater voter turnout. But it also could open up more targeted attacks if it were to become widely adopted, he says.

"The thing that scares me is when a particular population is targeted" and attackers study up on their common weaknesses and employ a systematic approach to wage cyberattacks on them, Wysopal says. Attackers could select a few swing-states or counties and set up waterholing attacks that discern their phone platforms and then drop exploits onto their phones.

Similarly, if the smartphone's presentation layer was compromised by a hacker, it could fool the voter into believing he or she had voted one way while instead the attacker voted for another candidate, notes Sam Curry, chief security officer at security vendor Cybereason.

"It could make 10,000 people in a critical district vote" unknowingly for a different candidate than they selected, he says. "You can't secure a phone presentation layer" completely, he says.

Mobile Voting Resumes

In the meantime, the newest Voatz mobile-voting pilots are kicking off in Oregon and Utah amid security concerns about this new method of voting. The University of New Haven's Baggili says just because you build an app from the ground up with security doesn't mean it's secure, and the blockchain itself may not be deployed securely.

"I could write malware impersonating the touchscreen on the phone, launch the app, and have it ask the voter to cast the vote for who they want to. It's hard to reverse that vote on the blockchain," he says.

He acknowledges that the mobile-voting experiments could, however, help shine a light on how to reach more voters digitally in a more secure manner, he says.

But there's one thing both sides agree on, besides the need for paper ballots to serve as a confirmation of a vote: Elections need better security overall to ensure votes are properly cast and counted — and that the outcome is trusted and provable to the candidates and voters. The two sides just don't agree on whether mobile voting can achieve that level of trust.

Related Content:

About the Author

You May Also Like

Cybersecurity Day: How to Automate Security Analytics with AI and ML

Dec 17, 2024The Dirt on ROT Data

Dec 18, 2024