Malware: The Next Generation

Zero-day and rapidly morphing malware is proliferating across the Web. Is your enterprise ready to stop it?

February 1, 2013

Download Dark Reading's February issue.

Download Dark Reading's February issue.

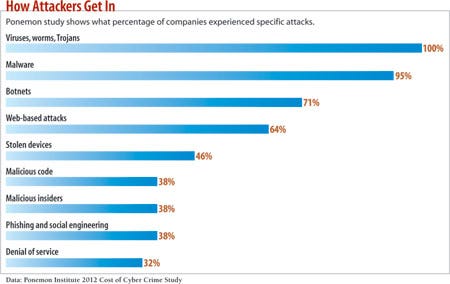

If January is anything to go by, then 2013 should be another doozy of a year for malware-plagued businesses. The year started off with the exploitation of a previously unknown Java vulnerability -- a spot-on example of why malware attackers are so successful these days.

The assault put millions of Java users at risk, as in many recent malware attacks, by taking advantage of flaws in a popular client-side application. In this case, it was Java's browser plug-in. But attackers often target other plug-ins, such as Flash, and document applications like Word and Adobe Reader. The January Java attack used a zero-day exploit, in which previously unknown vulnerabilities are targeted. Zero-day exploits are effective because victims wouldn't have patched to block them or spotted them via antivirus signatures, the digital fingerprints of known malware variants used to blacklist malware.

The Java attack let attackers gain control of vulnerable endpoints, potentially allowing them to launch attacks into any connected networks or simply to add infected devices to botnets that could be used to launch other attacks. Like so many malware attacks, this one was delivered using automated crimeware kits that let less skilled criminals infect websites with malicious code that automatically downloads from a website onto a visitor's machine (see "How Crimeware Kits Work").

Criminals can buy malware development services and software-as-a-service like the January Java exploit from a mature black market. For a few thousand dollars, they can get crimeware kits that let them launch automated attacks that run without any human intervention. And they're launching thousands of these sorts of attacks on enterprise infrastructures every day.

It's a crush of threats that most businesses can't stop with old regimes of firewalls, antivirus tools and occasional patching. Not only are the attacks coordinated using automated crimeware kits, but the malware itself has advanced to the point that it's able to evade signature-based detection regimes. And once an endpoint is owned by an attacker, it becomes a toehold into the network for further attacks on other resources, rendering the firewall irrelevant.

If IT departments are to protect their assets, their data and their customers, they must learn about how malware is evolving -- and how to keep up with the threats.

Several years ago, it was probably OK to focus more on basic threats, rather than the advanced ones, says Will Gragido, senior manager of the RSA FirstWatch Advanced Research Intelligence team at RSA NetWitness, the security intelligence and forensics division of RSA, and an 18-year veteran of the information security research community. The availability of attack tools is a big reason IT pros need to reassess the threats. >>

Getting Around Today's Defenses

Malware writers have gotten wise to the security methods companies and consumers are using --namely firewalls and antivirus tools. They've found ways to hide their malicious programs and operate quietly, avoiding detection. Once they get a toehold in a network, attackers quietly use infected machines in botnets, steal data from victims and drop more malware on the machines they attack.

Attackers have gotten good enough at these stealth attacks that at times can be on a network for months or even years without being detected. Last year, The Wall Street Journal reported that Nortel was compromised for 10 years without detecting it.

One simple way malware hides is by encrypting the payload on the user's machine or encrypting traffic to botnet servers, sometimes using custom encryption software designed by the criminal. Encryption can be combined with packer programs that change the appearance of the malware's binary code through compression algorithms similar to how a zip file works. Not only do packer programs reduce the size and footprint of malware on the machine, but the compression changes the lines of code in the application, making it easier for the malware to slip through the defenses of signature-based anti-malware scanners that detect malware based on how the executable code looks.

A lot of antivirus technologies have difficulty detecting packed malware because it changes the way the malware architecture is presented within the package. The packing schemes often are designed so that they'll only be "unpacked" and infect a user's machine if specific system state variables are met that trigger the malware's release. The malware might only run when a specific vulnerable application is opened by the user, effectively keeping it under wraps until then.

Encryption and packing technology aren't the only way malware developers stymie antivirus technology. They also develop polymorphic and metamorphic malware code that floods the Internet with millions of strains of malware each year in order to defeat the signature-based antivirus systems.

"You go to a website that serves you the malware, and typically about every 30 to 60 seconds the file -- the actual malware on that site -- is constantly shifting and changing its code to evade AV detection," says Derek Manky, senior security strategist and threat researcher at Fortinet Technologies, a network security and unified threat management firm. The constantly shifting code overloads signature-based systems. It's difficult to develop signatures for every single new variant that crops up, and as each signature is added to an antivirus program, that adds to the resources required to run it. Fortinet sees about 150,000 new malware samples a day, mostly due to polymorphism. "They're not all new viruses, but they're new forms of the virus," Manky says.

Polymorphism will start showing up in mobile malware, Manky says. Mobile malware is particularly scary given growing use of bring-your-own-device policies at companies. And then there's the threat of cross-platform malware.

"They're going to start consolidating malware so it's just one virus, one piece of malware," he says. "It doesn't care if it's running on your mobile device or on your PC. It's going to be much more integrated that way."

Cross-platform malware could take the form of cross-platform botnets and worms. For example an infected mobile handset comes onto a company network via Bluetooth, USB or other method and infects internal devices, using existing network connections to spread, Manky says.

(click image for larger view )

The Pyramid Of Sophistication

While the nastiest malware is growing in effectiveness and sophistication, the bulk of what's out there looks a lot like malware did years ago. That's because both consumer and business users are giving attackers little reason to advance their game to the next level. "If you look at what's actually being exploited, it's by and large the same vulnerabilities that have been exploited for the last five to 10 years," Gragido says.

The malware economy has stratified based on who the targets are and which adversaries are looking to attack them, says HD Moore, chief security officer for vulnerability management firm Rapid7 and chief architect of the Metasploit penetration testing framework. Think of it as a malware pyramid, with the least sophisticated and most frequent attack methods at the base and the very rare, cutting-edge targeted attacks up top.

The base level attacks are against consumers and lightly protected business endpoints that are behind on patches and have poorly updated antivirus tools or no security software at all. Attackers at this level aim to infect machines with online banking Trojans, keystroke loggers and other malware designed to steal credentials for identity theft, Moore says. Most online criminals make their money at this level, using cheap or free drive-by exploit kits.

The next level up is slightly more complex malware that spends more time propagating itself on the network once it has infected a machine, gathering more data and obfuscating itself more effectively. This level of malware is more exclusive and expensive.

Another level up the pyramid is where you run into higher-end exploit kits, Moore says. This is the level that most businesses should be concerned about. Organized criminals and industrial spies are the main perpetrators here, seeking to steal customer data and important intellectual property for financial gain.

These higher-level exploits are "designed to pull data out of businesses and do things like large-scale bank transfers or gathering customer databases," he says. "Granted, it's advanced compared to consumer-level malware out there, but it's not Stuxnet or Flame." >>

Stuxnet and Flame belong at the top of the pyramid. They're elite attacks created by state-sponsored purveyors for the sake of espionage and cyber warfare, Moore and other researchers say. Stuxnet, for instance, is generally believed to have been created by the U.S. government to attack Iranian nuclear reactors.

"With the really crazy stuff [at the top of the pyramid], there may be some commonalities among them in terms of how code is done, but they're not as widely available in dev kits, and they're not widely used against most of corporate America," Moore says.

It's that class of malware just below the top that should give enterprise IT leaders pause, Moore says.

At that level, the risk comes from the way the malware propagates, and how developers and attackers target specific online populations and are profiting from their crimes. The attackers usually are crooks running criminal enterprises, and they're looking to pay as little as they can for malware they use, so it doesn't eat into their profit margins. Zero-day vulnerabilities are expensive, so they're more likely to go with less sophisticated, cheaper methods like duping targets to open an infected email or visit an infected site, says Anup Ghosh, founder and CEO of Invincea, a breach detection platform developer.

"They don't want to pull out the 'A' team or the unused zero days if they don't have to," he says, but they are willing to do a lot research on their targets. They have the funding and the wherewithal to spend time trolling social media sites and conducting Google searches to dig up information about a company's employees that can be used to customize spearphishing messages designed to get a malware payload onto those employees' computers.

"They've got groups of people whose job it is to do nothing but go after these companies or organizations, get on their networks, search for what they're after and steal that data," Ghosh says.

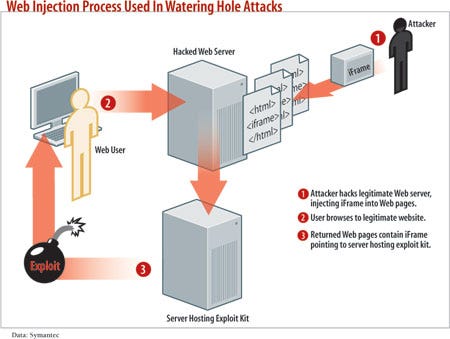

Attackers will even go so far as to set up watering-hole attacks where they infect a legitimate website that would be of interest to a specific type of employee in an organization. Bad guys have been infecting websites for a long time, but watering-hole attacks show criminals putting more thought and research into who they're attacking. For example, an attacker might buy malware designed to exploit an SAP accounting system, then try to infect the website of a U.S. accounting professionals' organization. Their hope is to infect visitors with a drive-by download of malware that lets the attacker take control of their machines and check to see if they have connections to the SAP systems the attacker wants to exploit.

"The concept of the attack is similar to a predator waiting at a watering hole in a desert," wrote Gavin O'Gorman and Geoff McDonald in Symantec's "The Elderwood Project" research paper. "The predator knows that victims will eventually have to come to the watering hole, so rather than go hunting, he waits for his victims to come to him."

Why can't you count on your antivirus software to detect and prevent the drive-by download malware? As mentioned earlier, attackers are using so many variants of code and methods of obfuscation such as encryption and packers that it's easy for malware to slip by AV programs.

(click image for larger view of the diagram)

Next-Gen Protection

As attack techniques progress, businesses need more than the existing methods of protection they've been using for years, such as signature-based technologies.

"Signatures of malware are like the TSA trying to use a photograph and fingerprint of every person in the world. In theory, it will work. But in this case, the fingerprint and the face keep changing," says Srinivas Kumar, co-founder and CTO of Taasera, a startup that offers detection techniques based on application behavior, rather than characteristics.

Security tools based on application behavior detection methods get rid of this problem. Rather than comparing what the code in an application looks like with a blacklist, as many traditional AV and endpoint security products do, behavior-based tools analyze how the application interacts with the system to assess whether the application is benign or malicious.

Behavioral detection methods try to deal with the problem of malware variants and offer some protection from zero-day attacks. The systems watch behavior and string together not just one behavior but multiple behaviors. "Did it open up the registry? Well, that by itself isn't so bad," says Brian Laing, director of U.S. marketing and products for AhnLab. "Did it write to the registry? That by itself isn't necessarily bad, either. Did it write to the run-once registry key? That's bad."

But even these methods require an understanding of the tactics attackers might use. Too many of the security industry's tools still rely on some kind of prior knowledge -- whether signatures, tactics, or URLs to avoid. For example, deep packet inspection generally uses a library or list of URLs known to be bad. And whitelisting technologies might depend on a cloud-based list of allowable functions to run. "That's all prior knowledge -- it's static and needs to be updated," says John Prisco, CEO of Triumfant, a malware analytics firm. Algorithmic-based tools that assess how a virus acts rather than what the code looks like are needed for a sustainable long-term anti-malware effort. "If you're not including more algorithmically based tools in your strategy, you're really fooling yourself into having this false sense of security," he says.

Businesses also must get serious about protecting their internal networks, says Rapid7's Moore. We've known for a decade that hardening networks with firewalls isn't enough, yet companies still leave their networks flat and unprotected inside the firewall. "The security of the internal network really starts to matter just as much as the external," Moore says.

Companies must segment high-value assets away from heavily trafficked parts of the network and institute more secure authentication and password management on endpoints and network assets. These steps create roadblocks to prevent the compromise of one internal machine from spreading to others.

For example, Moore points to a recent attack against oil company Saudi Aramco, in which 30,000 endpoints were compromised and damaged by hacktivists. There's been speculation that the victims shared passwords across all the desktops, something that's too common. "It's because of those kinds of fundamental security problems that these attacks are still happening -- and why people have to worry about malware on corporate networks," Moore says.

Segmentation doesn't have to be limited to the network. Many organizations are using virtualization and application sandboxing to provide a protective bubble against execution of malicious code. Applications run in a virtualized, contained layer above the actual system layer, creating a sandbox that keeps bad applications away from the root processes in the system.

Sandboxing isn't unassailable. Attackers can find vulnerabilities in the sandbox's parent process or in the operating system itself that let them neutralize the containment functionality, says Chris Valasek, senior security research scientist for application testing vendor Coverity. If hackers find a flaw in either one and run an exploit that lets them tinker with sandbox settings, they can allow their malware payload to escape the sandbox and execute functions at the system level rather than in the container.

"Windows kernel vulnerabilities are quite popular for privilege escalations because if exploited, they give the user total control of the system," Valasek says.

Malware is a moving and growing threat, and no one defense mechanism is going to neutralize it and completely protect businesses. A layered, integrated approach is most effective, one that uses a range of the different defense methodologies to keep wily attackers at bay. This "defense in depth" approach is more likely to be able to stand up to future malware no matter where the bad guys take the technology. That's a key advantage given that the scariest exploits are the ones we don't know about yet.

Sidebar

How Crimeware Kits Work

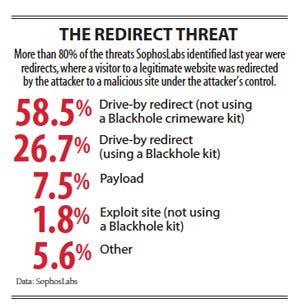

Crimeware kits are designed by professional hackers to automate the creation and propagation of malware.

They're sold to criminals who don't have the technical chops or the time to create their own malware. Operating under ominous names such as Blackhole, Cool EK, Nuclear Pack and Red Hole, these kits consist of ready-made programs that infectwebsites with malcode that automatically downloads from the website onto a site visitor's machine (referred to as a "drive-by download"). It then seeks out a specific vulnerability and exploits it. Many offer turnkey software-as-a-service subscriptions, giving users access to already infected sites and frequently updated exploit payloads. Crimeware kits cost anywhere from $300 up front to $10,000 a month as a service. Attackers use them to carry out malware campaigns that target specific user populations and vulnerabilities.

Malware kits were used liberally during last year's election, luring people to infected sites through election-related phishing messages. Criminals sent messages that looked like newsletters with links to CNN news articles that actually redirected readers to malicious links where the kit could take over and infect victims' machines.

-- Ericka Chickowski

About the Author

You May Also Like