A stealthy backdoor program used by China-linked threat actors has targeted government computers at multiple foreign agencies, allowing attackers to retain a presence on sensitive networks and exfiltrate data while remaining undetected.

February 28, 2022

A stealthy backdoor program discovered in tools used by China-linked threat actors has targeted government computers at multiple foreign agencies, allowing attackers to retain a presence on sensitive networks and exfiltrate data — while remaining undetected.

Researchers at Symantec, a division of Broadcom Software, said in an advisory issued today that the backdoor, which they have dubbed as Daxin, is "exhibiting technical complexity previously unseen." It gives attackers the ability to stealthily gather data on compromised systems and communicate the information to the attacker through machine-in-the-middle techniques. The malware — used as recently as November 2021 — has targeted government agencies in nations of strategic interest to China, Symantec stated, although the company did not name the organizations that had been affected by the malware.

The care with which the Chinese threat actors developed and used the backdoor differs dramatically from the standard programs and tools typically found by researchers, says Vikram Thakur, lead researcher at Broadcom's Symantec.

"This is the first threat that we have seen where they are conscious about long-term cyberattack campaigns for cyber espionage," he says. "In the past, Chinese threat actors have always seem to have little worry about being caught. We assumed that they treated their tools as one-use, but they have been [using Dakin] for over a decade, which means our original thinking was incorrect."

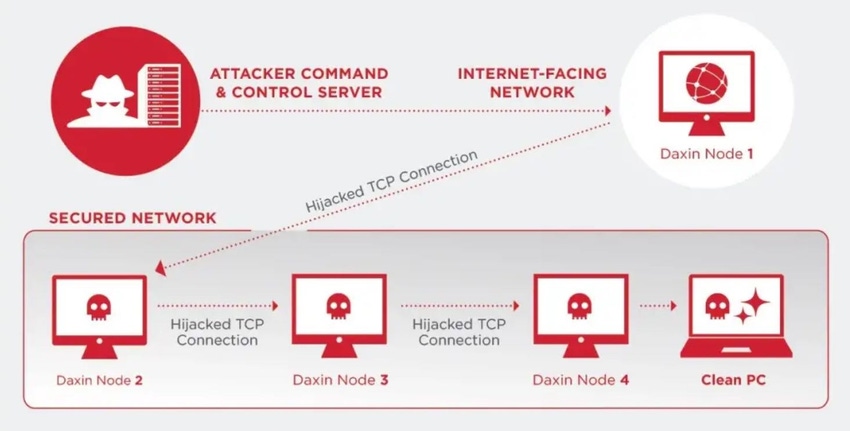

The backdoor is a Windows kernel driver implementing advanced communication features that allows its operators to infect systems on highly secure networks and let them to communicate without detection, even when the systems can't connect to the Internet. These features are similar to the Regin malware discovered by Symantec in 2014, and which the company attributed to Western intelligence agencies.

Symantec tracked the history of the Daxin backdoor back to 2013, with most of the advanced features already existing in the malware at that point, which "suggests that the attackers were already well established by 2013," the company stated in its advisory. The company believes that the intelligence group behind the malware existed at least as early as 2009, based on similarities to other programs.

"Daxin's capabilities suggest the attackers invested significant effort into developing communication techniques that can blend in unseen with normal network traffic on the target’s network," Symantec stated in the advisory. "Specifically, the malware avoids starting its own network services. Instead, it can abuse any legitimate services already running on the infected computers."

Daxin is a backdoor, which means that it allows the attacker to control systems infected with the program. The tool allows the attacker to read and write files and start and interact with processes — a small menu of features, but ones that allow full control of the system.

The true value of the malware for attackers is its ability to insert communications into legitimate network connections, monitoring all incoming data for specific patterns. Once it detects those patterns, Daxin takes over the connection and establishes a secure peer-to-peer network over the hijacked network link, at which point the backdoor can receive communications from the command-and-control network.

"Daxin takes it up several notches, because it seems to be designed for two specific purposes," says Symantec's Thakur. "It is designed to be used in long-term strategic attack campaigns. To achieve that, it does the second thing, which is to be as stealthy as possible: It does not open up any new ports; it does not speak with a command-and-control servers explicitly at any point at time."

China's Geopolitical Interests

Symantec attributed the program to China-linked threat actors. Circumstantially, the government agencies whose computers were infected by the program are considered to be in the geopolitical interests of China. More concretely, however, the systems compromised with Daxin also had a variety of other Chinese-associated tools and malware installed.

Symantec's parent company, Broadcom, worked with the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency to inform the affected foreign governments and help them find and purge the malware, the company stated.

Other companies will be hard-pressed to find the malware, as the program manages to remain quiet most of the time, Symantec's Thakur says. In its advisory, the company lists a number of indicators of compromise for companies to look for in their own networks.

"There is very little we can recommend besides from the standard, 'Here are some open source signatures you can through YARA or whatever solution you use,'" he says. "Because this driver sits in someone's environment and it has its own stack, it is really difficult for someone to eyeball and locate it. When we were dealing with remediating some victims, they had trouble even copying the driver off the system."

Thakur says that Symantec plans to publish more advisories with further analysis of the threat.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

Beyond Spam Filters and Firewalls: Preventing Business Email Compromises in the Modern Enterprise

April 30, 2024Key Findings from the State of AppSec Report 2024

May 7, 2024Is AI Identifying Threats to Your Network?

May 14, 2024Where and Why Threat Intelligence Makes Sense for Your Enterprise Security Strategy

May 15, 2024Safeguarding Political Campaigns: Defending Against Mass Phishing Attacks

May 16, 2024

Black Hat USA - August 3-8 - Learn More

August 3, 2024Cybersecurity's Hottest New Technologies: What You Need To Know

March 21, 2024