How Hackers Fool Your Employees

Attackers are taking aim at the weakest point in your network: human beings. Do you know how to protect your data?

April 11, 2013

Download Dark Reading's April 2013 issue

Pop quiz time: Which endpoint vulnerability is a hacker most likely to exploit to gain access to your enterprise network resources? It's not some unpatched Windows flaw or browser vulnerability. It actually isn't any technology at all. Your most vulnerable endpoint is the technology user a few cubes over.

People are nothing more than another operating system, says Lance Spitzner, training director for the Securing The Human Program at SANS Institute. "Computers store, process and transfer information, and people store, process and transfer information," he says. "They're another endpoint. But instead of buffer overflows, people suffer from insecure behaviors."

Hackers send phony messages crafted to look legitimate, and your employees click on the malicious attachments and links. The bad guys leave infected USB sticks in company parking lots that employees find and plug in just to see. Employees log on to compromised wireless networks to access corporate assets. There's a huge number of insecure behaviors along with a great many ways hackers exploit them.

Of course, your organization has anti-phishing technology to stop malicious messages from getting to users' inboxes, as well as vulnerability management suites that secure all those flaws that hackers exploit. And you have plenty of anti-malware software. But these products aren't perfect, nor are the deployments and practices around them.

Well-designed phishing messages stream past filters. The bad guys look for previously undetected technological vulnerabilities they can exploit with the help of unsuspecting users. They regularly develop new malware variants that anti-malware engines fail to detect. And they come up with sneakier ways to hide malicious software in messages and on the Web. In all these cases, the last line of defense is the employee who gets the malicious email or lands on the infected website. If companies don't address the vulnerable humans they employ, they're setting themselves up for failure.

Letting people fall into the mindset that the IT guys have this covered is what leads to a false sense of security, says Rohyt Belani, CEO of security training firm PhishMe. Most big companies that get breached inevitably are using anti-malware or anti-phishing software, he says, "so either the technology providers are lying to their clients or they're not 100% effective."

Penetration testers will tell you that most security failures come in the form of email, and their most powerful hacking tool isn't some low-level network exploit tool. "The most powerful pen test tool is Outlook," SANS's Spitzner says.

Ninety-one percent of targeted attacks between February and September last year involved spearphishing tactics, according to Trend Micro, an Internet content security vendor. Those attacks have evolved way beyond the bank phishing attacks of yesteryear. Attackers now take time to make detailed plans, research targets and develop or buy malicious exploits that raise as little suspicion as possible. If they can slip their attack mechanism past the victim's technical defenses, it can remain on the user's machine long enough for the attacker to make forays into the network it's connected to.

Conversational phishing is the latest attack trend. The victim gets multiple emails "that make it look like there's a human on the other end and that it's part of an email thread," PhishMe's Belani says. The attacker knows enough about the victim and his interests to convince him that, say, they had met at a busy convention such as RSA. From there, the attacker tells the victim about a blog post that he'd surely be interested in and attaches an infected version. The attacker even sends a follow-up message asking the user if he had a chance to look at the blog.

"Now you're subconsciously convinced that it's a real human being so you open that document," Belani says. "The bad guys have been doing that for at least the last six months."

And these attacks are becoming more sophisticated, says Mike Murray, managing partner for MAD Security, which does incident response and awareness training. In one instance about a year ago, a nation-state-level attacker went after an executive at one of MAD Security's clients, as well as four other executives at other organizations. The attacker did extensive research, likely on LinkedIn, and knew that the five executives regularly worked together on projects, Murray says. Using that knowledge, the hacker crafted five different emails, each of which looked like an email from one of the five colleagues to the rest of the group referencing a fictional meeting the recipient had missed. That message included a malicious attachment that was the supposed agenda for the fake meeting. Each email had a made-up thread to make it appear there had been a flurry of responses back and forth among the rest of the group.

"Tell me that you wouldn't have opened that? If it was five people you work with normally?" Murray says. "Every single person I know would have opened that, me included."

Social Engineers: Human Flaw Finders

Conversational phishing is just one of several social engineering tricks attackers use. On physical sites, they've dressed up as deliverymen to bluff their way into corporate buildings in order to plant key loggers, steal data-storing equipment and gather valuable intelligence. On the phone, they've posed as tech support people to fool users into spilling their corporate credentials. And online, attackers send spearphishing messages and flood search engines and social media with links to infected fake news articles.

Using these tactics, they manipulate users to stumble into attacks and take advantage of users' bad habits, such as reusing passwords. If an attacker can get his hands on a user's banking password through a phishing campaign or by compromising a bank's user-name and password database, and then find out where that user works, he may have what he needs to log into the corporate network.

5 security training essentials

Social engineers take full advantage of our proclivity to be complacent, SANS's Spitzner says. People aren't aware that they're targets, and they unwittingly help attackers by putting very public clues about themselves online, he says.

"It's people putting bits and pieces here and there, not realizing that when the bad guys harvest all that information, they now have a complete picture," Spitzner says. That picture lets attackers write emails full of cues that create a false sense of legitimacy.

People with a dominant public profile on social media stand a 50% greater chance of being spearphished than the average corporate user, Trend Micro says. Attackers aren't just conducting research on Facebook, LinkedIn and Twitter. They're combing through target organizations' websites seeking information they can use against employees, including partner announcements and logo lists boasting the company's high-profile clients.

"They have the time to do the research," says Tim Rohrbaugh, chief information security officer at Intersections, an identity risk management services provider. "They can figure out relationships between departments and managers through social media. They're reading filings, they're sorting out those partner lists and they're crafting messages that are very, very close to what a legitimate message would look like."

Even more troubling, features such as the Facebook Graph social search engine give hackers even more information to exploit, MAD Security's Murray says. He predicts that in just a few years, attackers will develop automated workflows to mine social graphs that craft phishing messages with very little human intervention. On LinkedIn, it's already possible to write a quick script that scrapes the service, grabs all the people a target knows and crafts phishing emails from them to you or you to them, he says.

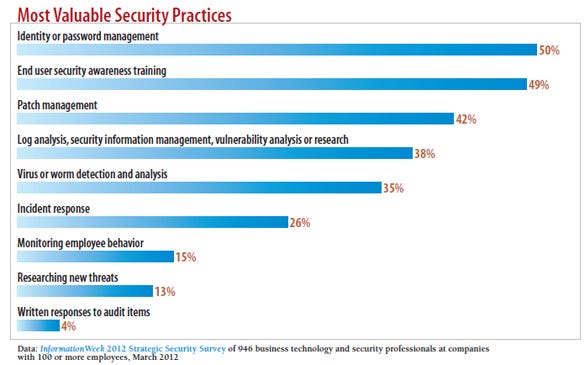

chart: most valuable security practices

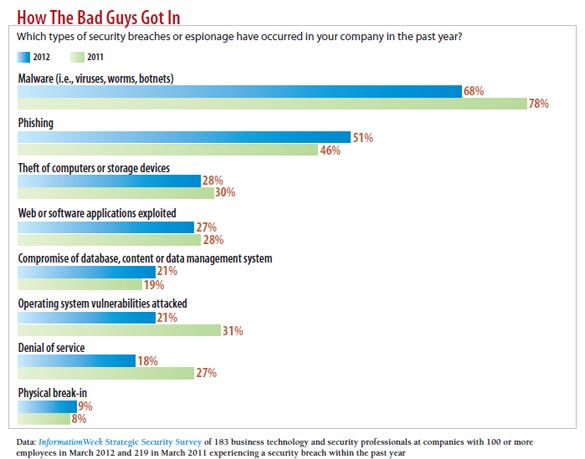

chart: what type of security breaches occured in your company in past year?

The Great Education Debate

The security community doesn't agree on the best way to counter social engineering attacks. Some experts say the answer is more user-awareness training. Others argue that awareness training has failed.

"I personally believe that training users in security is generally a waste of time and that the money can be spent better elsewhere," Bruce Schneier, chief security technology officer at BT, recently wrote on DarkReading.com. Users don't have a clear understanding of the threats, Schneier says. Instead of designing systems that force them to learn more complex ways of looking at their computers and the threats around them, we should design ones that conform to the way they currently view the threats, protecting them where they are. >>

It's a heated debate that can upset people on opposing sides. For instance, one RSA conference presenter conducted a class on "how to patch stupidity," Spitzner says. "He explained why people are stupid, how they're stupid and how to fix stupid. It was a very emotional talk for me, because how can you sit there and insult the very people who can end up helping us? That's something I'm desperately trying to change."

MAD Security's Murray offers another reason security pros have difficulty embracing the human element of defense: They're not people people. "Most of us were nerds. We got into hacking and all this geeky stuff because we didn't like people," he says. "We weren't captain of the football team or the popular kids in school, so we get really uncomfortable when someone says 'Security is a people problem. Go talk to your people.'"

Risk Mitigation And Early Detection

The truth is that no security tool, technical or otherwise, will eliminate 100% of the risks. But that doesn't diminish tools' power.

Cutting back on risk is a key goal of awareness training. Phishing susceptibility rates can fall to 8% from 58% through regular immersive training, whereby users are forced to deal with simulations of real threats, PhishMe's Belani says. With untrained employees, the attacker could send two emails and probably avoid detection, Belani says. "Now the attacker has to send more like 50 emails, and there's a chance that the technology will actually catch that," he says.

And with sophisticated spearphishing and scamming, the goal isn't prevention but early detection. "The faster you detect that really sophisticated attacker, the less time they have to really create a foothold and the more quickly you can get your organization into response mode and try to eradicate that infection," Murray says.

Take the executive conned by the fake email chain from four colleagues. The saving grace was that soon after the attack, he suspected something smelled rotten about the email thread and contacted his IT department.

Fostering such a mentality can turn those so-called stupid users into smart ones, Spitzner says. "These are scientists, doctors, lawyers, accountants, researchers. They're not stupid," he says. "It's just that we've never done a good job of educating them. When we teach them to detect and report, people become a detection system to improve organizational resilience."

Spitzner points to Mitre, a government contractor that develops the Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures list. Mitre has had great success with its own "human sensor awareness program." Employees now detect about 10% of the advanced attacks after they've slipped by technology defenses. That percentage may not seem like much, but considering that these are employees from all walks of life sniffing out attacks that most security technologies couldn't detect, it's a meaningful boost.

Companies don't always fully assess the effectiveness of their anti-phishing programs, Spitzner says. They look for a drop in the number of people who fall victim to phishing, but they don't count the dramatic increase in the number of phishing emails employees report.

Marketing Security

Turning "clueless" employees into effective human sensors takes patience, creativity and consistent messaging, elements missing from most security training programs. Employees generally take such programs when they're hired and then annually thereafter to satisfy regulatory requirements. But without patience, creativity and consistent messaging, these programs will fail.

You want to take advantage of teachable moments when people have just been burned, Rohrbaugh says. "Those are the times when you can make an evangelist for the security department," he says.

But don't wait around for bad things to happen. Institute incremental training that teaches employees how to spot phishing messages, the fundamentals of handling data securely, the basics of good password hygiene, and enough background on threats to persuade them to pay attention.

"We learn best through immersion and experience," Belani says. "So let's immerse people in the experience but do it in a controlled manner. When we're sending them a simulated phish, it's not like, 'Ah, got you, stupid!' We tell them: Anyone can fall for this. We're here to handhold."

Whichever method you use, it should be bite-sized and regular enough to make a difference. One word of caution: Message users with warnings and simulated phish email too often, and you risk losing their interest. And whatever you do, make the message interesting.

The very term "security training" sets the tone for snooze-worthy content, Murray says. It's why both he and Belani advocate that we take a page from marketers.

"We're not training our users. We're marketing to them," Murray says. "Marketers attempt to change the behavior of users with respect to how they buy things. We are trying to get them to 'buy' security. … In this case, my product is: Don't click on that link."

At the end of the day, whether you call it security marketing, behavioral modification or security awareness training, the goal is the same: Find ways to help users stop being so easy to fool.

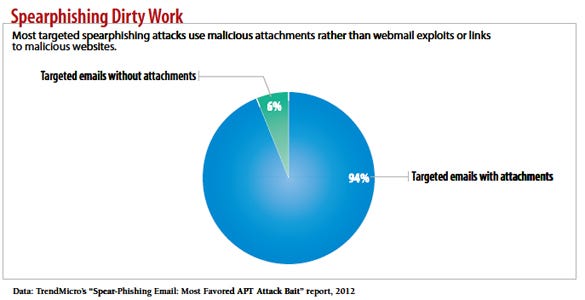

chart: targeted spear fishing attackes

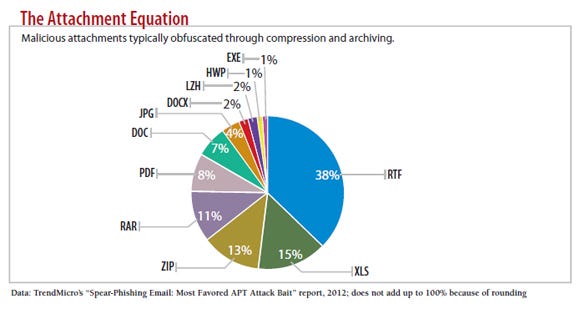

chart: malicious attachments

About the Author

You May Also Like