Endpoint Security

End user security requires layers of tools and training as employees use more devices and apps

May 30, 2013

Download the Dark Reading June 2013 issue

Download Dark Reading's June 2013 IssueWhen Meritrust Credit Union wanted to improve its endpoint security to comply with financial regulations, information security officer Brian Meyer needed to go beyond antivirus. The commonly used endpoint security typically doesn't provide a way of tracking whether employees' devices -- the laptops, tablets and phones moving in and out of the network -- have up-to-date security or are running potentially dangerous applications. With attackers routinely evading endpoint security, Meyer was legitimately worried that one might get in.

"Antivirus and some of the all-in-one suites that are out there are reactive, not proactive, so you're always behind the gun and playing catch-up to what's happening to your devices," Meyer says.

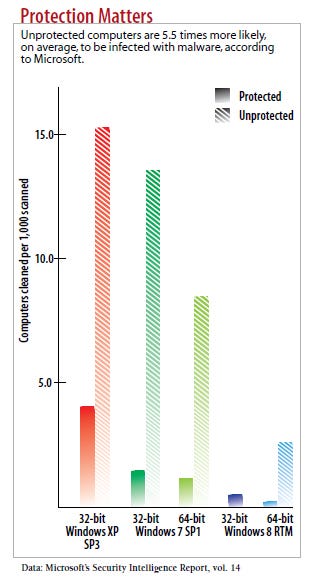

Antivirus has largely failed companies and consumers. The software does provide a base level of security -- systems with out-of-date security are 5.5 times more likely to have an infection than those running updated anti-malware software, according to Microsoft's latest Security Intelligence Report. But the ability of attackers to modify malware to escape detection and to test new variants against the top-selling antivirus scanners has made traditional signature-based antivirus software much less effective.

"Antivirus has been a Band-Aid for years," says Peter Firstbrook, VP of research with analyst firm Gartner. "They really never addressed the root cause of malware infections."

Just ask The New York Times. In January, the media conglomerate said that Chinese hackers had breached its security, gathering employee passwords and information on the sources reporters used in a story on the wealth accumulated by relatives of Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao. Using social engineering techniques, the attackers duped employees into allowing 45 different pieces of malware to infect company computers, but only one of those programs was identified as malicious by the Symantec antivirus software the company used, according to an article in The Times about the attacks.

"We're at the point now where the weakest link in the whole technological chain is the endpoint. It's where the hackers go when they want to break into an organization," says George Tubin, senior security strategist with Trusteer, a firm that focuses on securing endpoint applications.

In its response to the attack on The New York Times, Symantec said companies should turn on the advanced features of its products, such as website reputation and exploit-blocking capabilities. They stop 42% of all malware before it can run on a targeted system, the company says. "Turning on only the signature-based anti-virus components of endpoint solutions alone is not enough in a world that is changing daily from attacks and threats," Symantec said in a statement it posted after the article. "We encourage customers to be very aggressive in deploying solutions that offer a combined approach to security. Anti-virus software alone is not enough."

Most endpoint security software has now defaulted to turning on the most advanced features. But many companies turn them off, because they require the features to be tested for compatibility within their environment and because they believe there would be a large number of false positives.

The bring-your-own-device trend has turned these cracks in the antivirus model into dangerous holes. With employees bringing their own devices into work and working across desktops, laptops and mobile devices -- some personal and some company-owned -- the number of devices that need to be secured has soared. "There used to be a clear divide between what people did on their PC and what they did on their phone," says Candace Worley, senior VP for McAfee's endpoint unit. "Now there's complete fluidity in how people work no matter what device they're on."

Data on those devices is frequently shared among work and consumer devices and even uploaded into the cloud to services such as Dropbox and Box.net. This situation, combined with the success of attackers in getting around endpoint security measures, has security pros exploring new endpoint security options and devising alternative tactics to help harden devices and give control back to the IT security managers.

Build A Better Blacklist

Two approaches to securing endpoints from malicious software are to detect known bad software, known as blacklisting, or approve known good software, known as whitelisting.

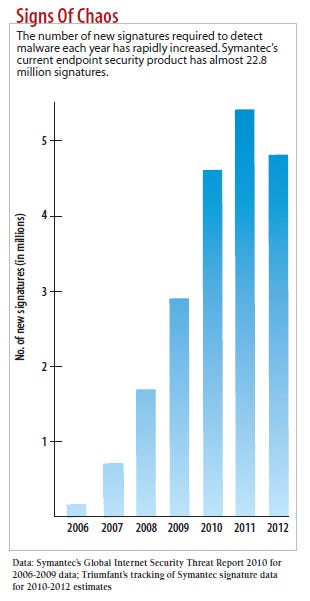

With blacklisting, employees can download and run any application that isn't banned. Blacklisting used to be more efficient than whitelisting because there were more good applications to track than bad ones. But recently attackers have overwhelmed security vendors' ability to maintain complete blacklists by generating millions of variants of their malware every month. In its 2012 Internet Security Threat Report, Symantec detected 403 million unique variants of malware, a 41% increase over 2011. (Starting in 2012, Symantec no longer reports this number.)

"I don't know if the problem is the hackers are getting smarter, or the hackers all know where the vulnerabilities are," says Srinivas Kumar, CTO at TaaSERA, a cloud security vendor. "They can make it very difficult to blacklist them."

Yet there are ways to improve blacklisting. The first is to focus on the initial download or attachment and the reputation of that file's source. Symantec uses a combination of techniques, such as website reputation and the blocking of exploits for known vulnerabilities, in its intrusion-prevention system, to stop malware from getting to the hard drive. Protection comes in layers: IPS blocks downloads, antivirus signature and heuristic technologies scan downloaded files, and behavioral detection tools block malicious behavior. The final step catches some of the most difficult-to-detect malware, says Michael Marfise, director of enterprise endpoint product management at Symantec.

Most malware today "changes so quickly that you can't generate signatures fast enough," Marfise says. "That's where you need technologies like reputation, so you don't have to wait for malware to be discovered."

Security vendors also link endpoints together to create something of a sensor network -- using information gathered from across the security vendor's customer base. When one endpoint detects a malicious file through behavioral analysis, information on the malware is passed back to the security provider, turned into a signature and available for download by the entire customer base through antivirus updates. By continuously updating information on suspicious files in this way, companies can more quickly react to malware.

Another improvement to blacklisting techniques is to continuously monitor files for malicious activity. A conventional antivirus tool checks files for signs of malicious activity just once, when it first encounters the file. Imperva, Sourcefire and Stegosystems are among the companies that watch for malicious behaviors on a continuous basis.

This idea of layered or continuous security changes security strategy by providing "lots of opportunities to analyze and detect something, rather than static analytics and detection that are 'one-and-done and I'm sorry if a missed something,'" says Marty Roesch, founder of Sourcefire, which bought cloud antivirus firm Immunet in 2011.

Walled Gardens

Whitelisting -- allowing the download only of approved applications -- has become more popular as attackers have gotten better at hiding the malicious files and applications. Like blacklisting, whitelisting is no longer just about comparing an executable file to a list of signatures. Instead of just approving application binaries, whitelisting has become a set of policies, says Harry Sverdlove, CTO for application control company Bit9.

Increasingly, whitelisting is about evaluating behavior and reputation and giving apps a score that places them on a spectrum. These evaluations take into account who's asking to run an application, says Randy Abrams, research director at security consultancy NSS Labs. An employee in accounting shouldn't be running a system administration tool, and a receptionist shouldn't be accessing a human-resources application. Managers may not want to allow consumer applications or sites such as games, Craigslist or dating sites on any of their employees' computers.

"There are really good apps out there that are perfectly harmless, but that doesn't mean they're appropriate for work computers," Sverdlove says. "Definitely, software apps that IT is using should never be on the accountant's computer."

Despite improvements, application whitelisting still poses management quandaries. For companies that want to give employees some freedom in what applications they run and where they go online, whitelisting can be a headache. "No company, or very few, could ever implement whitelisting for the Web," says Michael Gough, a senior security analyst for a midsize gaming company. "There are way too many sites to be able to manage this quickly and effectively. Can you really approve each and every executable or website or email recipient?"

Apple's App Store shows that whitelisting of a sort can work. The company has kept its iOS-based devices free of malware. While some malicious applications have evaded Apple's vetting process, the company has had almost no security incidents, even though researchers reported 387 vulnerabilities in iOS components last year. That record compares with Android's 12 security incidents despite having fewer vulnerabilities; more than a hundred malware lines targeted the mobile operating system in 2012.

Apple limited choice and reduced complexity, and it also reduced the chance of outside tampering. "You can't hack around with [iOS] like you can with an Android device," says Wendy Nather, research director for security at the 451 Group, an analyst firm.

Businesses could replicate the Apple App Store model by creating their own app stores and using mobile device management to keep their employees' devices secure.

Cage The Beast

Beyond whitelisting and application control, another approach is to isolate applications to keep malicious apps from infecting the device. Companies such as Invincea, Trusteer and Bromium are creating virtual containers for applications that limit the harm malicious applications can do and to potentially generate forensic data to analyze the threat.

Such systems run as kernel drivers, wrapping a specific application -- or in some cases all running code -- in a virtual container. When a program or file attempts to take a forbidden action, the virtual container blocks it. Rather than detecting bad behavior or focusing on suspicious programs, the software focuses on potentially dangerous actions, says Anup Ghosh, CEO of Invincea.

The fundamental difference between these kernel driver systems and behavioral detection is that with behavioral detection you have to detect the threat in order to protect the machine. "In a container-based approached, the threat always runs inside a container," Ghosh says.

Another technique to limit the risk of getting malicious applications on a device is wrapping applications in code that limits how they can be used and how they can handle data. Known as application management, the technique lets IT administrators control what applications are allowed on a device and how they handle data, even if the endpoint isn't company-owned.

Microsoft has taken a similar approach with its Information Rights Management system, which encrypts data into rights-protected documents and then issues licenses to authorized users to access the data.

To be effective, however, containers have to isolate threats from the system while letting workers share data and communicate. It's tricky to do: A virtual container that's too rigorous could prevent workers from saving and sharing data, while attackers will easily find their way around one that's too permissive.

Data-Driven Endpoint Security

Rather than focus on securing endpoints, other technologies aim to protect corporate data. "The moment you start touching the employee's device, a lot more complexity comes into play," says Suresh Balasubramanian, CEO of Armor5, a cloud security vendor that lets employees access corporate applications and data through a cloud service.

Technology such as virtual desktop infrastructure (VDI) lets users access data without allowing any malware on the endpoint access to either the data or the network, says Natalie Lambert, director of product marketing for Citrix, a networking and virtualization technology provider. "The data never resides on the endpoint, and so it can never be sent out," she says.

But VDI relies on an Internet connection. "The Internet seems ubiquitous, but it's not," says Brett Hansen, executive director of end user product strategy at Dell Software. "VDI is an option. It certainly provides a level of security, but it doesn't address how we work today."

Lock Down Access

Protecting the endpoint is largely about protecting corporate data, but it's also about protecting access to a company's network. The proliferation of devices and the erosion of the network perimeter have boosted interest in network access control technologies to bring order to amorphous networks, says Charles Henderson, director of the research labs at managed security service provider Trustwave. "Your mobile devices are coming and going. What's important is to make sure that your data isn't coming and going," he says.

Meritrust Credit Union had that problem. Rather than focus on protecting endpoints, it deployed a ForeScout NAC system to enforce its policies on all devices accessing its network. "The only way to make sure that every asset is meeting compliance is to have protection at the switch level, at the actual port that plugs in," Meyer says.

Network access control doesn't replace mobile device management, however. Companies interested in managing their fleet of smartphones should also deploy an MDM system -- many of which also provide security.

NAC enforces a company's policy on the device before allowing it to access the corporate network. The type of device and who owns it become less important than the provable state of the system, such as whether it's up to date on security software.

"The security that you put on or around the device -- maybe it's in the cloud, on the device or at the network edge -- needs to be aware of the device but focused on securing the applications and data," McAfee's Worley says.

With this view of the endpoint, you're less concerned with exact configuration of the device and more concerned with ensuring that the user is authorized for access and has taken good security measures, such as keeping the system up to date and not using known dangerous sites or applications. Other device features can be used in security as well: Location-based security in a hospital, for example, can let a device connect to a patient database as long as it has an authorized user who's logged in and located in the building.

Don't Forget User Training

Social engineering is a hard problem to solve with technology, so educating employees to understand threats is important.

"The brighter companies are going to start investing in education for their users to make the low-hanging fruit something you have to jump for, rather than walking by and picking it up off the ground," says Abrams of NSS Labs.

Because employees own an increasing number of the devices that they use at work, companies benefit from training staff to be more security conscious, Abrams says. Untrained employees are more likely to click on malicious links, fall prey to scams and not keep their devices up to date.

"When I have conversations with IT administrators, they're very motivated to make their end users happy, but those same users are putting them at a higher risk profile," says Dell's Hansen.

To help employees avoid making bad decisions, they must understand the risks and the reasons behind the policies. An employee who loses company data when his personal iPhone is stolen may be worried about pictures and other personal information he'll lose if his employer remotely wipes the phone clean and so delays reporting the theft for a week, says Armor5's Balasubramanian. If he realizes the implications from a security point of view, he's more likely to report it immediately.

Combine Forces For Better Security

There's little consensus on the future of endpoint security. Companies looking to cut security budgets would like one technique to secure all their endpoints, but that's unlikely to be adequate given today's focus on layered security, which forces attackers to go through successive layers of defense to get to valuable data.

In a recent research paper, Google researchers found that a combination of blacklisting, whitelisting and reputation-based malware detection uncovered malicious downloads that antivirus failed to detect. Standard antivirus scanners only caught 25% of the malware detected by the company's content-agnostic malware protection system, they said.

"You definitely still have to protect the endpoint, and you need a defense-in-depth strategy -- you need layers," says Patrick Foxhoven, CTO of emerging technologies at cloud security provider Zscaler.

Many endpoint protection systems already incorporate blacklists, some whitelisting, reputation-based browser protection and blocking based on behavior. Mobile device management can let IT wipe clean lost and stolen devices. NAC helps maintain minimum security standards on endpoints connecting to your systems.

Cost-sensitive security departments that would rather focus on a single technology could use a strategy of aggressive whitelisting, virtualization or enterprise rights management to protect data. But the price would come from reduced employee productivity and greater risk, and probably unhappy employees due to the restrictions.

The future of endpoint security is much more about combining and layering technologies. It comes down to making endpoint security less about protecting devices and more about controlling data and the applications that handle that valuable information.

Sidebar: BYOD Is Here To Stay

The upside to the bring-your-own-device movement is that it can reduce the cost of buying devices and produce happier and more productive employees.

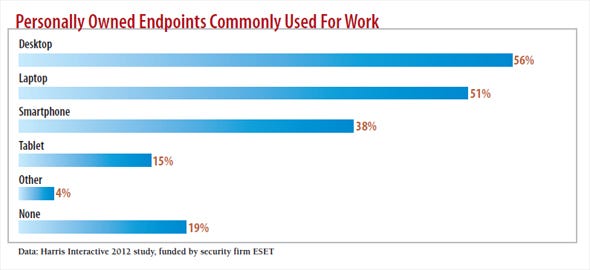

The main downside, however, is that companies lose control of the devices connecting to their network. And that risk is significant given that four out of five employees are using personally owned devices in some way for work, according to a survey conducted by Harris Interactive on behalf of security firm ESET.

"The diversity of devices out there will make it more costly to securely access data," says Randy Abrams, research director for NSS Labs, a security consultancy. Employees may be happier, but BYOD taxes IT departments and raises the cost of data security.

Yet trying to keep employees' devices off the network may prove futile. Even without much support from IT, 81% of workers used a personal device for work, according to the Harris Interactive survey. And with up-front device savings luring companies to embrace BYOD, it's unlikely the trend will lose steam, says Wendy Nather, security research director at the 451 Group, an analyst firm. "Companies should give up pretending that they own the devices," Nather says. "BYOD is a war that was lost from the beginning."

About the Author

You May Also Like