Researchers Show That Code Reuse Links Various North Korean Malware Groups

Analysts from McAfee and Intezer announced that by reviewing samples, they have found ties between campaigns and threat groups linked to North Korea.

North Korea came on the scene as a nation-state sponsored by cyberattacks in the mid-2000s and has rapidly increased its capabilities over more than a decade.

However, a months-long effort by security researchers from McAfee and Intezer is giving the industry an idea of just how broad the hermit country's reach is, showing links between well-known threat actors and high-profile campaigns over the past decade, including last year's WannaCry ransomware attacks.

The key to the research revolved around how the various known North Korea-based malware groups -- including Lazarus, Silent Chollima, Group 123, Hidden Cobra, DarkSeoul, Blockbuster, Operation Troy and 10 Days of Rain -- reuse code that can be found in various campaigns. The researchers also found a structure in which groups run by North Korea were filled with hackers with different skills and tools to execute specific kinds of campaigns, in particular to either steal money or attack other nations.

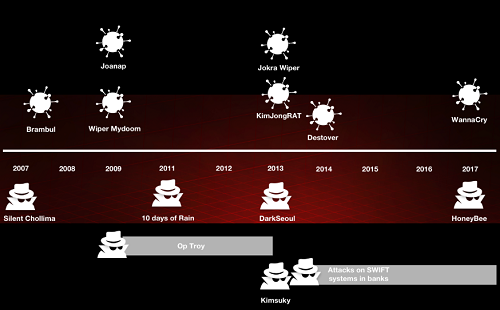

"From the Mydoom variant Brambul to the more recent Fallchill, WannaCry, and the targeting of cryptocurrency exchanges, we see a distinct timeline of attacks beginning from the moment North Korea entered the world stage as a significant threat actor," Christiaan Beek, lead scientist and senior principal engineer in the CTO office at McAfee, and Jay Rosenberg, senior security researcher at Intezer, wrote in a blog post. "Bad actors have a tendency to unwittingly leave fingerprints on their attacks, allowing researchers to connect the dots between them. North Korean actors have left many of these clues in their wake and throughout the evolution of their malware arsenal."

The two researchers talked about their findings at the Black Hat 2018 conference in Las Vegas.

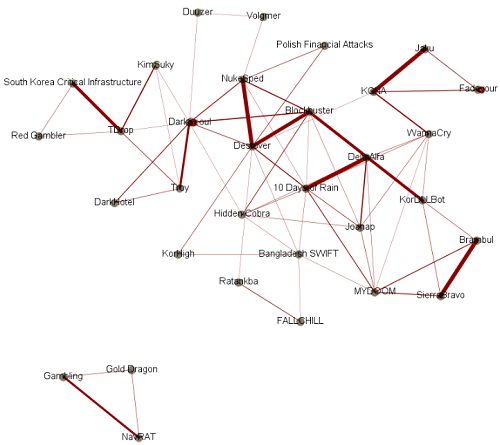

Beek told Security Now that it was well-known in the industry that groups associated with North Korea were reusing tools and code in their campaigns, but it was unclear how much this was being done and how far back it could be traced. He and Rosenberg began to example malware samples from North Korean campaigns. What they found through the code analysis were a number of similarities between samples attributed to North Korea, data hidden within the binaries and a shared networking infrastructure, as seen in the diagram below. The darker lines show deep code connections between malware campaigns.

North Korea-linked attacks

\r\n(Source: McAfee)

Examining North Korea

North Korea has been shunned by much of the rest of the world and its economy has been badly hurt by crushing sanctions. According to Beek and Rosenberg, orth Korea shares the same desire as other nations to be self-sufficient but it doesn't have the economic means, so its leaders have turned to illicit means of getting money, including cyberattacks. That effort has evolved into multiple cyber units with two primary focuses. Unit 180 works to acquire money for the country, including hacking into financial institutions, selling pirated and cracked software and hijacking gambling sessions. (See FBI & DHS Warn About 2 North Korea Malware Threats .)

The second aim -- conducted mostly by Unit 121 -- is to run campaigns driven by nationalism, which includes stealing intelligence from other nations or disrupting other countries or military targets. Beek said the attacks on financial institutions is fairly unique to North Korea among nation-states, but the sophistication and organization in North Korea's operations shows how quickly the country has evolved as a sponsor of cyberattacks.

"In 2006, they were starting to poke with simple DDoS attacks," Beek told Security Now. "If you now look almost ten years later, the cyber-offensive capacity of this nation has grown tremendously. It's one of the top countries right now with their cyber-offensive campaign... and [it's] using it as a weapon, on the one side to infiltrate and attack or to launch a destructive wiper, and on the other hand we see financial attacks that are meant to support the communist regime."

Beek and Rosenberg created a timeline of attacks attributed to North Korea and then began digging into the code. They noted that the first code example was a server message block (SMB) module of WannaCry in 2017 that also was used in Mydoom in 2009 as well as Joanap and DeltaAlfa. Other code shared by the families was an AES library from CodeProject, and all the attacks have been linked to the group Lazarus, which means the group has been reusing code from at least 2009 through 2017, they said.

Shared code

Similar shared code has been found in other samples from other campaigns.

North Korea timeline

\r\n(Source: McAfee)

The researchers noted that samples from a campaign discovered by Kaspersky Lab in 2014 targeted Asian hotels and used the malware family Dark Hotel. After examining Dark Hotel samples and those from North Korean campaigns, they found several areas of code reuse, including samples from Operation Troy. Analysts had known Dark Hotel was from a bad actor in Asia, but through the research, they were able to determine it was a North Korean operation.

"This research opens up a lot of ways of linking campaigns and probably attributing at some point as well," Rosenberg said.

There were questions about the origins of WannaCry, which infected hundreds of thousands of vulnerable Windows PCs worldwide, Beek said. Looking at the code, Beek and Rosenberg found that there were three versions of the ransomware -- a beta released in February 2017, another version in April and the infamous one in May. They determined they were developed in the same environment and likely by one actor. (See WannaCry: How the Notorious Worm Changed Ransomware.)

"With the code reusage, we saw multiple samples from different campaigns in the past that were pointing to WannaCry," he said.

The research could have far-reaching impacts, he and Rosenberg said. It could not only help in detection of attacks, but enable researchers to be more proactive in hunting for new malware. If something new is released, analysts have the resources to look at research indicators to see if the code has been seen before, Beek said.

"It's important to have as much information as possible about a threat," Rosenberg told Security Now. "The more information you have, the better chance you have to remediate or defend. Since we have so much information about previous DPRK [Democratic People’s Republic of Korea] campaigns, that makes us able to provide better solutions to the problem. One of these solutions is by detecting code reuse -- older malware that they're using in their campaigns or maybe an attack vector or C&Cs or IP addresses or domains. As I said about the Mydoom attack in '09, if we had created a signature from this shared, unique code, we could have detected WannaCry in 2017 immediately."

Related posts:

— Jeffrey Burt is a long-time tech journalist whose work has appeared in such publications as eWEEK, The Next Platform and Channelnomics.

Read more about:

Security NowAbout the Author

You May Also Like

Cybersecurity Day: How to Automate Security Analytics with AI and ML

Dec 17, 2024The Dirt on ROT Data

Dec 18, 2024