Allowing personal mobile devices at work can create new risks for your enterprise. Is your security policy ready?

Download Dark Reading's October issue.

Download Dark Reading's October issue.

Jesse Kornblum isn't your typical road warrior. As a computer forensics research guru (yes, that's his title) at Kyrus, a managed security services and consulting firm, he knows his stuff when it comes to information security.

But when traveling abroad, Kornblum is the first to admit that he's scared--or at least wary--that his security know-how won't be enough to protect him and his employer.

Take his upcoming business trip to Brazil. "Look, I'm a single guy, and Brazil is known for partying." It's likely that a new acquaintance or acquaintances will visit his room and have proximity to his phone or laptop, he says. Drive copying is a threat, as is outright theft of a device or information. A more sophisticated attacker might plant software on Kornblum's phone or laptop and monitor remotely.

Kornblum's concerns aren't the ravings of a computer forensics expert who has picked over the bloody remains of one too many network hacks. HD Moore, the CTO of security firm Rapid7, says that when he goes abroad, he brings a bare-bones netbook with data encryption installed and a BIOS and drive password enabled.

Moore also improvises anti-tamper features. He's been known to saw his netbook's case screws in half and pack the empty space in the screw holes with mashed Altoids to reveal if anyone had opened the device. Once when he left his netbook unattended in a Shanghai hotel room, he returned to find the powder gone from the screw hole and the BIOS password wiped, he says.

Like Kornblum and Moore, businesses everywhere are wrestling with security challenges posed by their increasingly mobile workforces. The reasons for this are clear: The workplace is undergoing its biggest transition since the desktop PC and client-server architecture displaced office mainframes more than two decades ago. This time around, it's PCs that are on the losing end to a ragged brigade of powerful, consumer-oriented mobile devices that include laptops, smartphones, and tablets in growing numbers.

The bring-your-own-device transition is transforming the workplace but also creating new risks for companies that plunge in without forethought and planning.

What's At Stake

A Forrester Research survey suggests that supporting employee-owned mobile devices isn't about letting people play Angry Birds at the office. More than three-quarters of employees who use smartphones at work and 63% who use tablets access their company intranet or portal sites using their mobile devices, according to a Forrester Research survey of 70 senior-level decision-makers at U.S., Canadian, U.K., and German companies. Fully 82% of those respondents say they use smartphones to read or view documents, presentations, and spreadsheets for work. Mobile enterprise users are going beyond Microsoft Outlook to tap into applications such as SharePoint, WebEx, and Documentum.

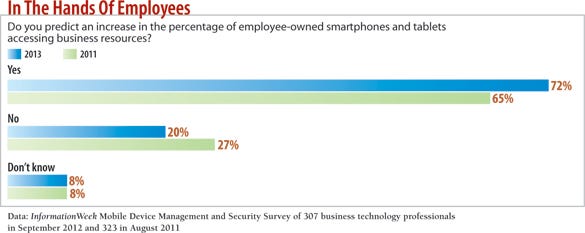

Businesses are throwing the doors open to mobile devices. Seventy-two percent of technology pros expect increased use of employee-owned devices accessing business resources, according to the InformationWeek 2013 Mobile Device Management and Security Survey of 307 business technology pros.

The transition to BYOD policies is happening across the board, with Apple iPads and iPhones and Android phones overwhelmingly leading the charge.

Unfortunately, the increase in employee-owned mobile devices hasn't been accompanied by security policies and tools to manage them. "Most companies still have no formalized policies," says Vanja Svajcer, a principal researcher at SophosLabs, the malicious code research group at antivirus software developer Sophos PLC. They might have existing policies for PCs, he says, and with BYOD, companies must either relax those policies or adjust them to accommodate mobile devices. That means having IT help employees connect their personal devices to network resources such as the office Wi-Fi network, the Microsoft Exchange email server, or a content management system.

Consulting firm PricewaterhouseCoopers found that 36% of the companies it polled in its 2012 Global State of Information Security Survey had a mobile device security strategy in place. Personal device use is the norm at Kyrus, but Kornblum admits that the company doesn't have hard and fast rules around employees' use of those devices. "We're a small company with fewer than 15 employees," he says. "We talk frequently about people not being stupid, and our business is examining how security goes wrong."

At less-security-savvy firms, the "give access now and secure later" approach can increase risk across the board, including everything from lost devices and stolen data to the use of vulnerable software and questionable apps.

Dude, Where's My Phone?

Lost and stolen mobile devices that contain sensitive company data are the biggest threat that companies allowing BYOD face, even though media attention is often on relatively rare mobile malware. Easily misplaced, with capacious hard drives and a laundry list of Web-based applications, smartphones and tablets--just like laptops--quickly become repositories for all manner of sensitive business information, from email messages to presentations to login credentials.

Securing those devices requires encrypting their hard drives and setting up strong passwords. But most phones aren't centrally controlled, says Al Huger, VP of development at cybersecurity company Sourcefire. "You need to have encryption and to have a standardized policy for passwords and for phones, but it's hard to enforce it without putting software on the endpoint."

However, installing a remote management application can be a sensitive issue when the device is owned by the employee, Huger says. Not everyone is going to want remote management capabilities controlled by their employers on their personal devices.

Data Theft: There's An App For That

Mobile applications--both legitimate and fraudulent--are a huge cause for concern at risk-sensitive firms. Mobile devices that have malicious or even just poorly coded applications installed on them are sources of insecurity.

Systems running Lookout Mobile Security's software detected 30,000 unique mobile malware instances in June, up from around 3,000 six months earlier, the company says. Mobile malware is still relatively rare but growing rapidly, since it has become a profitable business for cybercrime syndicates. One fast-growing category of mobile malware is so-called toll fraud programs. These abuse premium SMS messaging services on compromised phones by surreptitiously sending SMS messages to numbers that charge premiums back to the phone's owner. Mobile threats are likely to increase in the future, Lookout says.

Sourcefire's analysts commonly find malicious mobile software, particularly on Google Android devices, that's "causing mischief" on corporate networks, Huger says. Infected mobile devices use Bluetooth and other means to scan corporate networks for data to steal and other devices to infect. Smartphones look different from laptops, but, under the hood, they're still just computers, he says. "A jailbroken iPhone is just a Unix host," says Huger, referring to the mobile operating system's roots in Apple's Unix-based OS X. "You can log in to it remotely over SSH [Secure Shell]. Once you're in, you can use it to scan the public IP network."

An even bigger threat to companies comes from legitimate, nonmalicious applications--many of them not work-related--that can subtly and unintentionally expose company data and resources to prying eyes.

Aaron Turner, a co-founder and principal at the security consulting company N4Struct, says audits of his customers' networks have revealed these sorts of dependency problems.

"Let's say that a company lets mobile devices' native contacts, email, and calendar be connected to the Exchange server," Turner posits. "Now suppose that the LinkedIn mobile app requests permissions to view and copy all of your contacts. Is the enterprise really OK with LinkedIn getting a full copy of its global address list? That's pretty much the problem space right now: rogue apps interacting with enterprise data in ways that not everyone understands."

Lookout CTO Kevin Mahaffey describes the BYOD risk as "unquantifiable" because mobile application use creates "downstream risk" that's hard to predict. "If someone uses a weak password for Windows, the company will care. But what if their Dropbox account has a weak password, too? Now, the strength of everyone's passwords are a corporate concern," he says. Mobile devices, coupled with fast broadband connections and cloud-based services, mean every password that employees use now matters to their employers--not just the ones used to access corporate assets.

One Policy To Rule Them All

Lost devices? Vulnerable software? Dodgy applications? What's a risk-conscious company to do? The experts we spoke with have some suggestions.

Ideally, consumer-owned mobile devices would be governed by the same policies that apply to other company assets, such as laptops, desktops, and servers. But there really isn't "one policy to rule them all," and each company has to craft its own BYOD security policy. There are four common approaches that will help make your company more secure.

1. Know your enemy (and your friend)

The bare fact is that IT security practices at many companies are already porous and prone to failure. The anxiety about the risk caused by consumer devices may dial up executives' anxiety about data loss and infections, and that might be a good thing.

"I see the debate about BYOD as a forcing function that's making corporations take their internal security seriously and take steps to reduce their attack surface," says Rapid7's Moore, creator of the Metasploit penetration testing tool. In a BYOD environment, that might entail a philosophical shift in the thinking about mobile devices.

"Pay attention to phones and tablets," Lookout's Mahaffey says. "They're valuable corporate assets that hold sensitive email and documents, as well as internal applications." If users were more aware of that vulnerability, they might treat phones with more care--more akin to a wallet than replaceable electronic gadgets, he says.

Companies need visibility in two ways: They need to know what devices employees have and how those devices affect their risk, says Matt Dean, chief operating officer at FireMon, a security management software company. "You want to manage and control the risk that you're exposed to, so if a mobile device shows up on your wireless network, you understand what risk it poses to your network," he says.

2. Reduce the attack surface

Another step in securing BYOD environments is reducing exposure to attack. Companies should pay less attention to niche mobile attack vectors and concentrate on the security of their office environment's Wi-Fi infrastructure, Rapid7's Moore says.

The office Wi-Fi networks that those bandwidth-hungry mobile devices are tapping into are the real security Achilles' heel at many companies, Moore says. "Forget about mobile devices. If you have some massive Wi-Fi leak with rogue access points on your network, an attacker can own your machine and other corporate assets without doing anything else," he says.

Companies might consider disabling Wi-Fi within the office--though that's not going to make employees happy or productive. More tolerable might be to isolate Wi-Fi networks that mobile devices use from the rest of the company network, and provide strict filtering and policy enforcement for devices connected to them. For example: Use Web filtering tools to block access to potentially dangerous or non-work-related websites, and intrusion-prevention software or mobile device management tools to block network access altogether for noncompliant devices.

Regular audits of your Wi-Fi infrastructure are a good idea to make sure employees or attackers haven't set up rogue access points and to spot suspicious wireless traffic in or out of the network.

3. Set the rules

If you experiment with BYOD, you must consider where and how to enforce the rules, says Sophos's Svajcer. Do you want to allow every type of new device on your network but curtail access to resources, or provide more extensive access to select devices that meet security standards?

Mobile device management software is a fast-growing area of interest and investment. Gartner counts more than 100 companies in the enterprise MDM market worldwide. MDM vendors include large IT services and security companies such as IBM, SAP, Sophos, and Symantec, as well as specialized firms such as AirWatch, Good Technologies, and Zenprise.

Depending on the package you go with, MDM software and services let you set policies across a range of mobile device hardware and software platforms. They enforce strong passwords and application downloading and patching, as well as detect jailbroken devices, and provide auditing and remote wiping and locking for lost and stolen devices.

Some MDM vendors are introducing data monitoring capabilities that give businesses a window into what data is moving to and from managed mobile devices. Vendors such as Zenprise also offer "geofencing," which lets IT detect when devices leave a certain geographic area and take action to secure them (such as locking or remotely wiping data on the device).

Companies also are finding alternatives to an all-or-nothing approach to BYOD that encourage productive use of mobile devices but retain a measure of control.

One such approach is enterprise mobile application stores, in which businesses provide access to company-approved mobile apps for download by employees, while using mobile security policies to prevent unapproved applications from being installed on managed devices.

Startups such as AppCentral, which has Pepsi and Anheuser-Busch as customers, provide services that let companies control and manage their employees' access to custom mobile applications. Similarly, Cisco's AppHQ platform helps companies create their own internally hosted application stores.

Branded mobile application storefronts can go a long way to easing enterprise concerns about application integrity and corporate control. In the long term, however, Sourcefire's Huger believes that the BYOD trend may come back full circle to LYDAH (leave your device at home).

Whether employees like it or not, security and management require employers to run software on employees' devices. As noted previously, that can be a sensitive issue when the employer doesn't own the device. Companies can skirt the issue by supplying employees with attractive mobile devices loaded with the necessary security and management tools.

"I've started to see exactly that," Huger says. "I have a customer who just purchased 500 iPhones for employees. They spent a lot of money to do it, but it's cheaper and more effective to control the software on the devices," he says. "In the long term, you just can't have these powerful devices unrestricted and loose on your network."

Employees may be more amenable to that approach than all the BYOD talk suggests, according to Forrester data. A Forrester Forrsights Workforce Employee Survey of 322 enterprise users from the fourth quarter of 2011 found that, while 45% of respondents would like to have their choice of mobile phone or smartphone, only 23% would be willing to contribute to the cost of the device in exchange for choice. Fully 32% of those surveyed say they "don't care" about choosing their own work mobile phone or smartphone.

4. Confront the issues

Finally, while companies should take seriously the risks of BYOD, they shouldn't overcorrect for the perceived loss of control that employee-owned devices create.

"You want to have sensible, but not restrictive policies," Mahaffey says. "The most important thing is to empower people to be productive."

Don't take the "slumlord approach to network security," says Johannes Ullrich of the SANS Institute in an article he wrote for the Forbes website. Like landlords for low-rent apartments, Ullrich says, many network administrators remove or disable features that could potentially cause security problems, rather than incur risk by letting employees benefit from those features. By overreacting to perceived risk, those administrators create rules-bound IT environments that can crush workers' souls--especially younger, digital natives. Like stripped-down apartment houses, those restrictive, punitive IT environments drive away creative employees and encourage those that remain to circumvent security features, rather than live with them.

BYOD is a great example of embracing reality rather than fighting it. Employees are going to use their own devices anyway, so it's better to support them, Ullrich says. Rather than crack down on non-company-owned devices, he says, "it may be more secure to set up a dedicated network for these devices that's controlled and managed versus having employees work around these issues."

Education may, in the end, be the simplest, cheapest, and most effective tool that companies can use to reduce the risks employee-owned devices pose. Talking to employees about mobile threats and the importance of using passwords to secure physical access to devices, as well as encryption to protect the data that's stored on them, is critical, especially in the absence of corporate-wide policies and tools to enforce them.

Rather than banishing employee-owned devices, smart organizations will embrace them and learn how to address the security shortcomings. "Don't freak out and stop people from using their phone," says Mahaffey. "Confront the issues and deal with them." That approach puts you in control of the devices on your network, ensures that employees are well educated about potential problems, and makes it less likely they'll sneak devices on the network or otherwise violate policies.

Sidebar: Five Tips For Better BYOD Security

Letting employees bring their own devices onto the company network doesn't have to be complicated, says Kevin Mahaffey, CTO and a co-founder of Lookout Mobile Security, which makes security software for mobile devices. He suggests five simple steps for an effective BYOD security program.

1. Have sensible, but not restrictive, policies. Emphasize user education about the threats posed by lost, stolen, and infected mobile devices and enforce reasonable policies such as requiring a PIN code to get physical access to a mobile device used on the company network.

2. Implement remote lock, wipe, and locate features on company- and employee-owned devices. There are any number of mobile device management packages that offer these kind of remote features, and device location and remote wipe come standard with newer versions of Apple's iOS software.

3. Install anti-malware protection. It's still early days for mobile malware, but the trend lines point sharply up and to the right. Better to be safe than sorry: Install mobile anti-malware now.

4. Road warriors should use VPNs for everything when connecting to company assets from mobile devices, especially when connecting over public Wi-Fi.

5. Focus on authentication and identity. Strong passwords aren't enough, especially when keylogging malware and man-in-the-middle attacks may be present. Multifactor authentication or federated identity should be used to access high-value services on the company network. --Paul Roberts

Sidebar: Mobile Device Security On The Road

HD Moore invented the Metasploit testing platform and is CTO at the security firm Rapid7. He's also notoriously paranoid about getting hacked--quite fitting for someone who makes a living poking holes in others' defenses. Moore has several practical tips for business travelers:

1. Beware of Wi-Fi. Moore recommends turning off Wi-Fi on your phone, tablet, and laptop. If you have to use the hotel or other Wi-Fi, be aware that you're at risk the second you connect, he says. There's a "window of opportunity between when you authenticate to the captive portal and when you bring up the VPN that leaves your traffic at the mercy of anyone with a netbook and a shell script."

2. Turn off Bluetooth. Nearly all Bluetooth headsets are insecure and can be used to listen in on private conversations. Bluetooth services on laptops can expose security weaknesses and even your file system.

3. Connect to your corporate VPN as soon as you can if you have to use an untrusted network. This puts your traffic in "full tunnel" mode, making it difficult for hackers to sniff or use man-in-the-middle tactics from the local network. If the VPN connection drops, close out Outlook and any sensitive applications until the connection is re-established.

4. Keep a close eye on your equipment. Never leave laptops, bags, or notebooks with sensitive information out of your sight.

5. Don't share files with strangers using USB keys. You have no idea what they are giving you, and by letting someone borrow your key, they can easily copy all of the data off the drive, even deleted contents from the free space. --Paul Roberts

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

The fuel in the new AI race: Data

April 23, 2024Securing Code in the Age of AI

April 24, 2024Beyond Spam Filters and Firewalls: Preventing Business Email Compromises in the Modern Enterprise

April 30, 2024Key Findings from the State of AppSec Report 2024

May 7, 2024Is AI Identifying Threats to Your Network?

May 14, 2024

Black Hat USA - August 3-8 - Learn More

August 3, 2024Cybersecurity's Hottest New Technologies: What You Need To Know

March 21, 2024