Apple's Rapid Security Response updates are designed to patch critical security vulnerabilities, but how much good can they do when patching is a weeks-long process?

May 31, 2023

Apple's recent release of macOS Ventura 13.4 contained a laundry list of security fixes, including two WebKit vulnerabilities that could lead to leaks of sensitive information and remote code execution. Apple's security notes acknowledged that they were "aware of a report that this issue may have been actively exploited," which is as close to an acknowledgment of an in-the-wild exploit as we're likely to get.

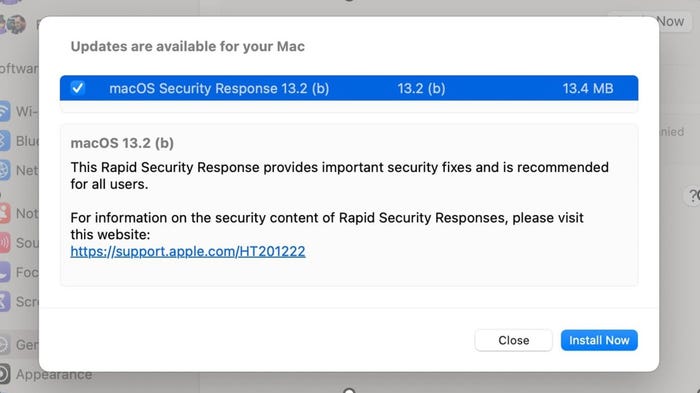

These are the kinds of critical fixes that make IT and security teams scramble to get updates installed, but it turns out that those WebKit issues had already been patched in Apple's first Rapid Security Response (RSR) update on May 1.

Source: MacRumors (https://www.macrumors.com/2023/01/09/apple-macos-ventura-13-2-rsr-update/)

The inaugural RSR release didn't exactly go off without a hitch, and users didn't even know what it contained until the operating system (OS) release. Still, introducing RSRs is a positive development because they decouple urgent security patches from bulky OS updates that are released less frequently and take longer to install.

On the other hand, the very existence of RSRs is a tacit acknowledgment from Apple that their security needs are increasingly urgent — the types of exploits that can't wait weeks or months to be fixed. And that should get the attention of everyone concerned with Mac patch management since "waiting weeks or months to install patches" is precisely what IT admins are accustomed to doing.

Apple Patch Management Tools Fall Short

Broadly speaking, IT teams have two options for installing updates and upgrades across their Mac fleets, and neither of them entirely solves the problem.

The first option is to remotely install updates through mobile device management (MDM), which requires a forced restart of a user's device. This option is effective in theory, but in practice, it's so disruptive to users that most admins are reluctant to employ it. Even when you warn users of updates ahead of time and schedule them during the dead of night, any forced restart is a potential data-loss event, and many users (including executives and developers, who often present major security risks) will get themselves exempted from this policy.

The lesson here is: You need the participation of end users to install updates and upgrades.

The second option is to use tools like Nudge, which, as the name suggests, pesters users to install patches by sending them automated reminders. These reminders increase in frequency and intensity until they finally take over the user's screen. This approach offers admins some help, but users still tend to defer updates for as long as possible, and the vast majority allow deferrals of 30 or more days.

The lesson here is: You can't simply ask end users to update — there must be consequences for noncompliance.

Finally, both the MDM and Nudge options only work on supervised devices. If you're talking about a BYOD Mac or a contractor's device, organizations have no way of enforcing patching whatsoever.

To Fix Patch Management, Change User Habits

There's an unfortunate tendency among IT and security professionals to dismiss the potential of end users to be security allies rather than liabilities. And it's true that it's not easy to convince users to take updates seriously. That may be particularly true for Mac users, who (until recently) have been largely immune from the kinds of security threats that plague the Windows community.

But there are lessons from other movements that successfully changed seemingly intractable behaviors. A particularly instructive example comes from seatbelt laws.

It's easy to forget, but getting Americans to buckle up in the 1980s was nearly as challenging as getting them to install updates is today. At the time, many felt that seatbelt laws were an example of socialist government overreach. But today, Americans accept seat belts automatically (except in New Hampshire, where there's still no law).

Changing seat-belt habits required a blend of solutions. On the technical level, automakers were required to include seat belts in all vehicles. Meanwhile, Americans were convinced to use them through a mix of public education (public service announcements and billboards) and proportional consequences (fines).

The same mix of solutions can change user behavior around patch management. Technical solutions include automated tools that reduce the friction of updates and provide visibility even into unmanaged devices. But these must be accompanied by education since many users don't understand that promptly installing updates is one of the most impactful security measures they can take. Finally, any approach must include proportional consequences to users, such as being unable to access company resources until updates are installed.

Regardless of how IT and security teams choose to implement this approach, it's clear that change is needed. At the very least, Apple shouldn't be releasing patches faster than IT admins can deploy them.

Here's a video that demonstrates how to put these principles of patch management into practice.

About the Author

Elaine Atwell is Kolide's senior editor of content marketing. She has been writing about enterprise security since 2019 and is interested in security approaches that balance responsible data management with employee privacy and autonomy.

You May Also Like

The fuel in the new AI race: Data

April 23, 2024Securing Code in the Age of AI

April 24, 2024Beyond Spam Filters and Firewalls: Preventing Business Email Compromises in the Modern Enterprise

April 30, 2024Key Findings from the State of AppSec Report 2024

May 7, 2024Is AI Identifying Threats to Your Network?

May 14, 2024

Black Hat USA - August 3-8 - Learn More

August 3, 2024Cybersecurity's Hottest New Technologies: What You Need To Know

March 21, 2024