Many organized cybercrime gangs operate beyond European and US borders -- or jurisdiction -- thus making online crime eradication impossible.

10 Ways To Fight Digital Theft & Fraud

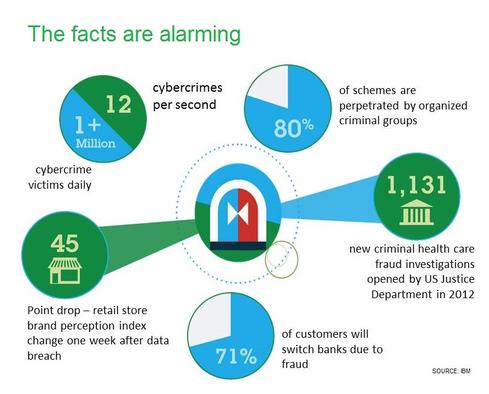

10 Ways To Fight Digital Theft & Fraud (Click image for larger view and slideshow.)

Should European cybercrime investigators triage more cybercrime cases and pursue fewer low-level cases while devoting greater resources to taking down the biggest organized crime gangs?

That suggestion was voiced in the opening keynote presentation delivered at this week's Infosecurity Europe conference in London by Troels Oerting, head of the European Cybercrime Centre (EC3) and assistant director for the operations department at Europol, which is the EU's law enforcement agency.

"We might also have to say no to some cases, like we do with bicycle theft," said Oerting. "There might be some cases that police do not prioritize, simply because we prioritize where the greatest harm is."

As anyone who's ever been the victim of bicycle theft knows, the police hardly launch an investigation every time someone files a complaint. But Oerting suggested that, with the quantity and severity of online attacks increasing, cybercrime cops should more purposefully allocate their scarce policing resources for maximum effect. Still, with so much online crime being -- by its very definition -- borderless, and increasingly disguised via anonymizing networks, would resource reallocation really take a big bite out of crime?

"Criminals can attack anyone, anytime, anywhere," said Oerting. "I'm getting gray hairs, because most of the criminal activity is being done via the darknet... which not even the NSA can penetrate."

[AOL warns subscribers to change passwords, be wary of all email from AOL addresses. Read more: AOL Subscriber Data Stolen: You've Got Pwned.]

According to Europol, Europe loses about €1.3 billion annually to credit card fraud alone.

Furthermore, online attacks against European targets continue to rise. According to a report issued this week by security firm FireEye, based on the 40,000 unique attacks and 22 million pieces of malware command-and-control communications the company saw at customers' sites in 2013, the four most malware-targeted European countries were Great Britain, Switzerland, Germany, and France -- accounting for 71% of all infected European systems.

Meanwhile, the advanced persistent threat (APT) attacks seen by FireEye primarily targeted Germany and the United Kingdom, with federal government agencies, energy firms, and financial services businesses the primary targets in what is typically a long-running operation. "Each APT event is an element in a long-term campaign against an organization in an industry -- try, try, try," said Simon Mullis, European systems integration technical lead at FireEye, in an interview at Infosecurity Europe. "You want to be careful, because when the APTs stop, they're already in."

According to data released earlier this month by Mandiant's FireEye, the average breach goes undetected for 229 days -- if it gets detected at all. In 67% of cases where breaches were detected, it was thanks to a third party, such as the FBI or Europol.

Europol's Oerting said his organization has been helping the 28 EU member countries bolster their information security investigation capabilities. "We've built up a heavy forensic capability to help the member states by assisting them in evidence-gathering."

Might better tools help, too? While acknowledging discussions in Britain, where elements of the coalition government would like to distance the country politically from the EU, Oerting lauded the EU for helping countries work together, not least when it comes to combatting crime and making related research and development funds available. "The EU has allotted €80 billion for research and development, and I intend to grab some of this money in order to ask the 28 member states: What types of tools do you need? Then we use the money, and give the tools back to the member states."

Then again, the origin of so many of today's online attacks won't be tough to trace. "My department works with Russian language speakers in about 75% to 80% of all our cases," Oerting said. But one long-standing challenge is that neither Russia nor Ukraine, which many security experts see as the biggest safe havens for criminals who launch online attacks, have extradition treaties with either Europe or the United States.

It's still tough for European or US police to catch criminals that foreign governments won't extradite. In computer crime cases involving Russian-language speakers, for example, Europol sometimes shares case information with its Russian counterparts and hopes local police follow it up. "Or we do it in the good old-fashioned police way -- we wait until they leave, and then we capture them," Oerting said.

But trying to arrest cybercriminals goes only so far. "We will not prosecute our way out of cybercrime," Lee Miles, deputy head of the UK National Cyber Crime Unit, which is part of the country's recently formed National Crime Agency, said Wednesday at an Infosecurity Europe panel discussion. "Many of the issues are jurisdictional," he noted, referring to the difficulty of prosecuting people in countries such as Russia. "Many of them are the sheer volume and anonymity, and many are the low-level individual crimes that don't really rise into organized criminality."

Given limited time and resources, accordingly, don't expect police to be able to pursue -- or prosecute -- every criminal who targets people online.

Cyber criminals wielding APTs have plenty of innovative techniques to evade network and endpoint defenses. It's scary stuff, and ignorance is definitely not bliss. How to fight back? Think security that's distributed, stratified, and adaptive. Read our Advanced Attacks Demand New Defenses report today. (Free registration required.)

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

The fuel in the new AI race: Data

April 23, 2024Securing Code in the Age of AI

April 24, 2024Beyond Spam Filters and Firewalls: Preventing Business Email Compromises in the Modern Enterprise

April 30, 2024Key Findings from the State of AppSec Report 2024

May 7, 2024Is AI Identifying Threats to Your Network?

May 14, 2024

Black Hat USA - August 3-8 - Learn More

August 3, 2024Cybersecurity's Hottest New Technologies: What You Need To Know

March 21, 2024