Cybercriminals are actively exploiting ProxyShell vulnerabilities CVE-2021-34473, CVE-2021-34523, and CVE-2021-31207. Here's what to do about this.

The Department of Homeland Security's Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) along with several members of the security research community are warning of active attacks exploiting ProxyShell flaws CVE-2021-34473, CVE-2021-34523, and CVE-2021-31207.

Researchers at Huntress began observing a growing number of Microsoft Exchange Servers targeted with a ProxyShell attack chain on Aug. 20. Since its original notice, the count has grown from about 100 infected servers to a current 370, says senior security researcher John Hammond. He notes this is not, however, a repeat of the ProxyLogon vulnerability and Hafnium threat seen in March.

"Unlike the vulnerability in March, we are not yet seeing a centralized, organized, and large-scale attack … but all of the puzzle pieces are available and this situation could turn into that," Hammond explains. As of Aug, 24, Shodan reports 20,674 Exchange servers in the US alone that are vulnerable to CVE-2021-34473, an element of the ProxyShell attack chain, he points out.

CVE-2021-34473 is a Microsoft Exchange Server remote code execution vulnerability with a CVSS 3.0 score of 9.1 that requires no privileges or user interaction to execute code. CVE-2021-34523 is a Microsoft Exchange Server elevation of privilege vulnerability with a CVSS 3.0 score of 9.0. Attackers can use it to execute code, post-authentication, due to a flaw in PowerShell not properly validating access tokens. CVE-2021-31207, with a CVSS 3.0 score of 6.6, is a post-authentication flaw that allows an attacker to run code in the context of NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM and gain administrative access.

Attackers are chaining these three vulnerabilities together to perform unauthenticated remote code execution, and they only need access to the public-facing Web service of Microsoft Exchange, hosted on port 443. "With simple Web requests to /autodiscover/autodiscover.json, threat actors could leverage unsafe functionality to perform this ProxyShell attack," he says.

Huntress is focused on the novelty of the Web shells used in these attacks. In August, researchers have seen at least five unique styles of Web shells deployed to vulnerable Microsoft Exchange servers, Hammond writes in a blog post. These include XSL Transform, which is most common at more than 130 occurrences, in addition to Encrypted Reflected Assembly Loader, Comment Separation and Obfuscation of the "unsafe" Keyword, Jscript Base64 Encoding and Character Typecasting, and Arbitrary File Uploader, he explains in a blog post on the exploits.

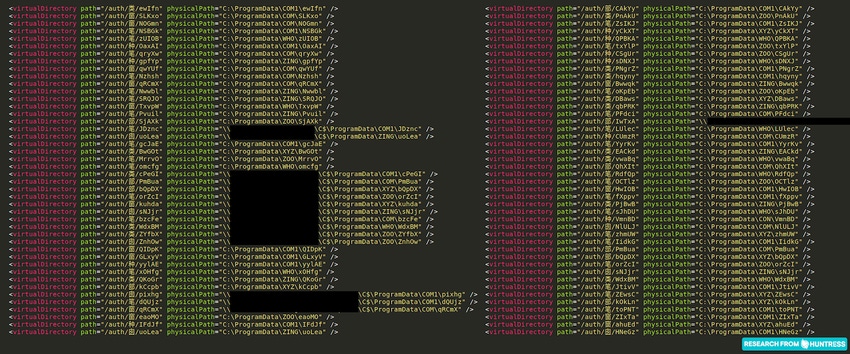

A new trick in the ProxyShell attacks involves the attackers modifying Exchange configuration file applicationHost.config.

"In the modified configuration file, attackers slyly slipped in a new 'virtual directory' setting, which tells the server to host files from a different location on the file system," he says. "With that in place, the bad actor could hide new webshells in a non-standard location."

Researchers have seen hidden Web shells in C:\ProgramData in a folder that has a unique name, often matching a reserved filename in Windows that can't be easily changed. Filenames like COM1 or LPT1 may deceive automated prevention tools, which then bypass malicious files. Huntress has seen about 90 hidden Web shells on 60 endpoints, some with multiple instances.

With a Web shell present and server compromised, researchers observe "what seems like only the beginning" of post-exploitation, Hammond says. Some machines hit with ProxyShell have cryptocurrency miners deployed; one victim was hit with the LockFile ransomware. Both actions point to attackers who are motivated by financial gain, he notes. Only a handful of devices have shown signs of post-exploitation other than leaving a Web shell for future access.

Regarding the LockFile attack, Hammond notes that one case doesn't indicate a correlation between the broader ProxyShell attacks and LockFIle ransomware. That said, anecdotal reports from other researchers state that other cases of ProxyShell and LockFile have been seen in the wild. After speaking with affected organizations, Huntress learned the LockFile ransomware allegedly began a few days ago, which would align with the uptick in ProxyShell exploitation.

How Businesses Should Respond

Much like ProxyLogon, this vulnerability is publicly exposed and accessible to anyone on the Internet, meaning attackers can scan the Web looking for vulnerable Exchange Servers.

Huntress has seen small businesses compromised across multiple industries: building manufacturers, power product suppliers, seafood processors, industrial machinery, auto repair shops, jeweler businesses, real estate, dental and law offices, and dairy farms, among others. One attack affected a small residential airport; another affected a yacht club. No single region or industry has been a victim – the targets are anyone running an unpatched Exchange server.

"There is some chatter and confusion about what patches should be applied, or how this differs from ProxyLogon in March – this is not to be confused with ProxyLogon, and the mentality 'we patched in March' will not suffice in this situation," Hammond says.

It is worth noting that Microsoft has stated the vulnerabilities were patched in April and May, which aligns with CISA's guidance advising organizations to apply Microsoft Security Update from May 2021. But while all three of the ProxyShell vulnerabilities were patched earlier, it wasn't until July that patches were announced and CVEs assigned, explains security researcher Orange Tsai, who discovered the flaws. Huntress is advising businesses to update and validate their Exchange servers are patched up to the July 2021 security release.

Exchange Server has been in the spotlight this year, Hammond says, and the security must remember this is not a siloed incident. Going forward, organizations must stay on alert so they're aware of vulnerabilities and new attack surfaces that may not be publicized by the original provider.

"Keep up to date with threat intelligence, monitor for indicators of compromise, and be a part of the community that is working towards better security," Hammond says. "Response to incidents like this, even larger or even smaller, takes the whole industry playing in concert."

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

Securing Code in the Age of AI

April 24, 2024Beyond Spam Filters and Firewalls: Preventing Business Email Compromises in the Modern Enterprise

April 30, 2024Key Findings from the State of AppSec Report 2024

May 7, 2024Is AI Identifying Threats to Your Network?

May 14, 2024Where and Why Threat Intelligence Makes Sense for Your Enterprise Security Strategy

May 15, 2024

Black Hat USA - August 3-8 - Learn More

August 3, 2024Cybersecurity's Hottest New Technologies: What You Need To Know

March 21, 2024