The zero-day attack business is no longer just about money, and patching is no longer the best defense.

A successful drive-by shooting requires planning, timing, effective weapons and a quick exit (or so I’m told by friends who play Grand Theft Auto). In the cybersphere, zero-day drive-by attacks succeed based on the same criteria, but unfortunately the fast escape is rarely required.

Exploit packs are the core commodity that facilitates drive-by attacks for global cyber criminals. Since 2005, when Mpack was first released, over 100 individually marketed exploit packs -- with names like Black Hole, Neutrino, and Sweet Orange -- have been sold to leverage the World Wide Web and to exploit victims’ computers. The exploit pack itself is literally a bundle of exploits for known vulnerable software neatly packaged with an administrative web interface. Exploit packs are purchased in the criminal underground and installed on web servers where the owners periodically check their instance’s drive-by efficacy.

Once an exploit pack is installed, an attacker must push victim web traffic to the exploit pack site. These days there are numerous methods to compromise web pages and redirect unsuspecting visitors. Top 10 Google search results (via thousands of newly generated and linked blogs), advertising and content delivery networks, popular blogs, and even large news sites are regularly compromised. One second a victim is reading the news and the next his/her system is seamlessly redirected and probed for software vulnerabilities.

That’s where it starts. The applications we all use and love (think Adobe Reader, Oracle’s Java, Microsoft Office, and all four of the major web browsers) must be constantly updated. When these applications aren’t patched, drive-by exploitation happens instantly and some hideous piece of malicious code (adware, malware, crimeware, ransomware) ends up on a victim’s computer. Drive-by attacks really are insidious because they require only that victims browse the web and criminals are only too happy to abuse the landscape where millions of potential victims roam.

Exploding demand

As a result, demand for new and improved exploit packs is constantly expanding. Exploit pack authors are forced to update their crimeware services with new exploits as soon as new software vulnerabilities are announced or risk losing hard earned criminal market share due to an obsolete product. So like any profitable software company, authors write an exploit once (or copy it from the helpful Internet), update the exploit pack, license it on a per server basis, and continue to watch the e-currency stack up.

Unfortunately the drive-by business is no longer just about money. It turns out that hard working 9-5 nation state actors are already receiving a pay check with a government insignia on it. These men and women are concerned with political intelligence gathering and intellectual property theft for the purpose of competitive advantage on a grand scale.

It didn’t take long for these nation state actors to realize that they could improve upon well established and successful criminal attack vectors. The original derivative work was spear-phishing. This turned mass market criminal phishing attacks - sent without regard to the recipient’s identity - into highly targeted emails sent to extensively researched individuals. Naturally these emails include attachments or links relevant to the target victim in order to entice them to act. This technique was (and continues to be) incredibly effective on all kinds of government and industry verticals.

After years of successful network compromises and data exfiltration with spear-phishing, these foreign government employees decided to add another strategy to the playbook: the watering-hole attack.

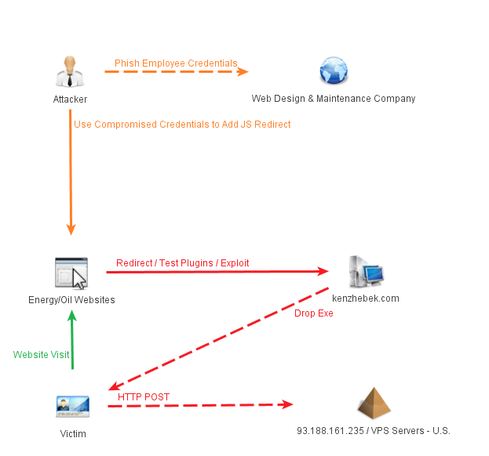

Figure 1:

Similar to a criminal drive-by, the watering-hole attack redirects unsuspecting victims; the difference is that the redirection (usually via obfuscated JavaScript) is placed on a carefully chosen website where the intended victim will likely browse in the course of their daily employment activities. Indiscriminately exploiting victims is pointless for nation state actors, rather it is a select group of targets that must be compromised in order for the attack to be deemed a success (which for them may entail a better-than-average holiday bonus).

Further, because the intended victims’ computers may be fully patched, nation state actors don’t need a full exploit pack. Instead they can rely on one or two zero-day exploits. (A “zero-day” is security industry jargon for exploit code that targets a previously unknown software vulnerability.) Since government resources are exponentially larger than criminals’, zero-day exploits are purchased from third party brokers or developed internally and used in watering-hole attacks to increase the chances of success.

Two such attacks occurred in May. The first campaign compromised the US Department of Labor’s Site Exposure Matrices (SEM) website -- a very specific watering-hole -- and injected JavaScript code which redirected visitors to dol.ns01.us. Naturally, this website was hosting a zero-day exploit for Internet Explorer (CVE-2013-1347). Following successful exploitation a Remote Access Trojan (RAT) was installed on the victim’s computer.

Subsequent attacks occurred in the same fashion days later when oil and energy company websites were modified to host redirection code. Ten oil/energy sites redirected victims to three different websites hosting exploits. In fact the same Department of Labor Internet Explorer zero day exploit was used in tandem with a Java (CVE-2012-1723) and Firefox/Thunderbird (CVE-2013-1690) exploit. While a zero-day exploit doesn’t remain zero day for long, it is a powerful tool with plenty of potency for quick and targeted campaigns.

Figure 2:

Unfortunately the use of zero day-exploits in drive-by attacks appears to be accelerating. In the past two months different zero-day exploits for Internet Explorer were discovered as part of larger strategic web compromise attack campaigns. In the most recent attack a RAT was installed on victim computers and in October Microsoft released a security advisory citing a different Internet Explorer vulnerability that was actively being exploited in Asia.

It’s evident that governments, businesses, and individuals are all at risk for drive-by attacks. When dealing with the criminal set and their exploit packs the answer has always been, patch! Since exploit packs historically bundle large amounts of shell code corresponding to known vulnerabilities, the most efficient method for "p0wnage" prevention was a robust vulnerability identification and security patch management program. Zero-day exploits make this defensive strategy obsolete. So the question becomes what is the answer when comprehensive patching is no longer the solution?

A sensible answer is behavior scoring because there are plenty of common malicious indicators between recent attacks. One practical way to implement the scoring is via a web proxy, specifically to fetch and preview web content before serving it to the requestor. The presence of obfuscated JavaScript code, redirection tags, shell code, and dynamic DNS domains can all be scored, and any content above the tolerance threshold should be rejected before it impacts the end user. Nevertheless, nation state attackers’ behaviors and methodologies will evolve and new defense strategies will need to be implemented.

Finally, it’s not the end of the world if a watering-hole attack succeeds, so long as network (and ideally host) security monitoring programs detect the breach before the company or agency’s intellectual property crown jewels are removed.

Drive-by attacker’s planning and timing can’t be prevented, but we can remove the weapon’s effectiveness.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

Defending Against Today's Threat Landscape with MDR

April 18, 2024The fuel in the new AI race: Data

April 23, 2024Securing Code in the Age of AI

April 24, 2024Beyond Spam Filters and Firewalls: Preventing Business Email Compromises in the Modern Enterprise

April 30, 2024Key Findings from the State of AppSec Report 2024

May 7, 2024

Black Hat USA - August 3-8 - Learn More

August 3, 2024Cybersecurity's Hottest New Technologies: What You Need To Know

March 21, 2024